| Detail | Hard Disk |

|---|---|

| Name | Hard Disk Drive (HDD), a magnetic random-access storage device |

| First Commercial System | IBM 305 RAMAC with the IBM 350 disk storage unit |

| Who Built It | An IBM team led by Reynold B. Johnson |

| When It Shipped | June 1956 (first customer shipment of the IBM 350 as part of RAMAC) |

| What Made It New | Direct access to stored records without scanning a whole tape; a practical form of random access |

| Early Capacity | About 5 million characters (often cited around 3.75 MB) on large spinning platters |

| Core Principle | Bits are stored as magnetic orientation changes on a rotating platter, read by a tiny head |

| Main Moving Parts | Platters, spindle motor, actuator, read/write heads |

| Typical Modern Sizes | 3.5-inch (desktop/NAS), 2.5-inch (laptop/portable), plus enterprise variants |

| Common Interfaces | SATA (most consumer), SAS (many servers), USB (external enclosures) |

| Where HDDs Shine Today | Low cost-per-terabyte, big archives, backups, home NAS, and many data centers |

| Key Limits | Mechanical latency, sensitivity to shock, slower small-file access than SSDs |

A hard disk is a precision machine built for stable storage: it keeps your data on spinning platters using magnetic patterns that stay put even when power is off.

What A Hard Disk Is

An HDD stores information by writing tiny magnetic changes onto a rotating platter. A moving head reads those changes back as bits, turning physical states into digital data you can use.

Why It Became A Big Deal

- Random access means the drive can jump to a needed location fast, without reading everything before it.

- Rewritable magnetic media lets data be updated in place on the same platters.

- High density keeps improving, so an HDD can hold massive libraries in a compact box.

Where It Fits Today

- Large backups where capacity matters more than instant speed.

- Media libraries (photos, video, projects) that need room at a sensible cost-per-TB.

- Always-on storage in NAS boxes designed for steady, predictable workloads.

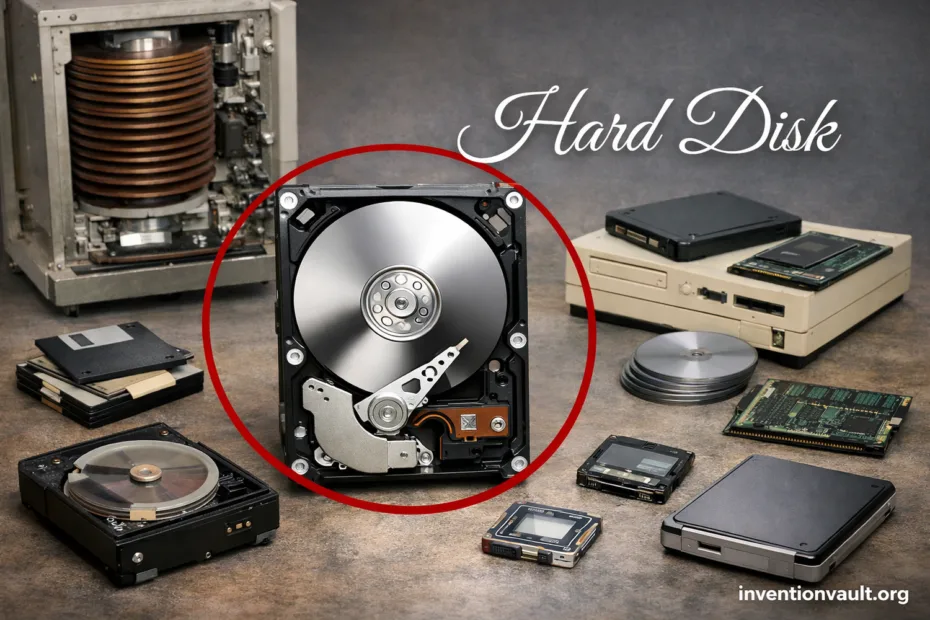

Core Parts Inside A Drive

Open a hard disk and you’ll see a clean mechanical layout where each part supports accuracy. The goal is simple: keep the heads aligned, keep the platters stable, and keep timing consistent.

Platters

A platter is usually an aluminum or glass substrate coated with thin magnetic layers. The surface must be extremely smooth so the head can fly just above it without touching.

Heads and Actuator

The read/write heads sit on a lightweight arm moved by a voice-coil actuator, a design that behaves like a speaker motor. This setup lets the drive position the head with fine control across thousands of tracks.

Spindle Motor and Bearings

The spindle motor spins the platters at a constant RPM. Stable rotation reduces timing drift and helps the drive maintain consistent reads, even when the head is chasing data across different zones.

Controller Board and Cache

The controller is the drive’s brain. It manages error correction, maps physical locations to logical addresses, and uses onboard cache to smooth out bursts of reads and writes. Good firmware can make day-to-day use feel more steady.

How Data Lives On A Spinning Disk

Data is arranged in circular tracks divided into sectors. Modern drives present a clean, simple view called logical block addressing so your system can ask for block numbers without caring about the exact geometry. Under the hood, the drive still optimizes where bits live for speed.

A Typical Read Request

- Your system asks for a block of data at a logical address (LBA).

- The drive’s controller translates that request to a track and position on a platter.

- The actuator moves the head (seek), then the platter rotation brings the right sector under it (rotation).

- The signal is decoded with error correction, then returned to the computer.

| Term | What It Means In Practice |

|---|---|

| Seek | Time for the actuator to move the head to the right track |

| Rotational Latency | Waiting for the platter to spin the right sector under the head |

| Sequential Transfer | Fast reading/writing of long, continuous data on nearby tracks |

| Random I/O | Slower access to many small files scattered across different areas |

Major Recording Methods

Not all hard disks record data the same way. Two drives can look identical from the outside while behaving very differently once you push heavy writes or steady mixed workloads. Paying attention to the recording method helps match the drive to the right job and keeps performance more predictable.

CMR and SMR

CMR (Conventional Magnetic Recording) writes tracks side by side, which keeps rewriting straightforward. SMR (Shingled Magnetic Recording) overlaps tracks like roof shingles to fit more data per platter, yet large write bursts can trigger extra background work and feel slower in some scenarios.

| Recording Style | Typical Strength | Typical Tradeoff |

|---|---|---|

| CMR | Steady performance under repeated writes; friendly to many multi-drive setups | Lower density than SMR at the same platter count |

| SMR | Higher capacity at attractive cost-per-TB for calmer write patterns | Write-heavy workloads can feel uneven due to track overlap management |

PMR and Beyond

Many modern drives use perpendicular recording to pack bits more tightly by changing how magnetic regions are oriented. Newer approaches, including heat-assisted techniques in the industry, aim to push density further while preserving reliabilty and readable signal margins on the platter.

Helium-Filled Designs

Some high-capacity HDDs replace air inside the enclosure with helium. Because helium is less dense, internal drag drops, which can support more platters, lower power draw, and cooler operation in tight shelves. These drives are sealed and tuned for large capacity with efficient rotation.

Interfaces and Form Factors

The outside connector shapes what a drive can plug into, while the physical size influences how many platters can fit and how well heat is managed. Most everyday systems see SATA drives, while many servers rely on SAS for features built around continuous operation and strong device management.

Common Form Factors

- 3.5-inch drives often target maximum capacity per device.

- 2.5-inch drives fit tighter spaces and portable enclosures, with lower power needs in many designs.

- External HDDs usually pair an internal drive with a USB bridge for easy connection.

Main Interfaces

- SATA is widely used for consumer storage with a simple, familiar ecosystem.

- SAS is built for enterprise drive shelves and robust multi-drive operation.

- USB is common for portable and desktop external HDDs, adding convenience through plug-and-play.

| Interface | Where You See It | What Stands Out |

|---|---|---|

| SATA | Desktops, many home NAS boxes, budget servers | Cost-effective storage, wide compatibility, straightforward setup |

| SAS | Servers, data centers, enterprise storage arrays | Designed for 24/7 use and advanced drive management features |

| USB | External drives, backup disks, portable libraries | Convenience and portability, depends on enclosure quality and controller |

Performance Measurements That Matter

Hard disks can feel fast in one task and sluggish in another. That’s not a mystery: HDD performance is shaped by movement (seeks), rotation, and how neatly data is laid out on disk. Knowing what each spec affects helps set real expectations without overselling numbers.

| Metric | What You Notice | Common Context |

|---|---|---|

| RPM | Lower latency for many operations, smoother sequential reads | Often seen in desktop (e.g., 5400/7200) and enterprise classes |

| Cache | Snappier short bursts when data repeats or arrives in chunks | Helps with small buffering moments, not a substitute for low latency media |

| Seek Time | Responsiveness when many small files are scattered | Impacts random reads/writes more than large transfers |

| Sustained Throughput | How fast large files move, like video exports or archives | Often strongest on the outer disk zones, shaped by platter density |

One detail people miss: an HDD can deliver strong sequential speed while still feeling slow with many tiny files, because each new file may trigger a fresh seek and extra rotation.

Reliability and Care

A hard disk is designed for years of service, yet it’s still a mechanical device. Heat, vibration, and sudden physical shocks can reduce the margin a drive has for precise head positioning. Good systems treat HDDs as valuable tools: they keep them cool, stable, and monitored with SMART health data.

Common Stress Factors

- Shock while spinning can risk head contact with the platter.

- Heat can increase error rates and shorten component life over time.

- Vibration can disturb fine head positioning, especially in multi-drive bays.

What Monitoring Really Does

- SMART attributes can flag rising reallocated sectors or read errors early.

- Regular checks help you spot a drive trending unhealthy before it surprises you.

- Monitoring supports calm maintenance planning rather than last-minute panic.

Hard Disk Variants You Will See

“Hard disk” is one family name. Inside that family are designs optimized for different environments: quiet home storage, always-on NAS units, and high-vibration server shelves. The differences show up in firmware, vibration tolerance, and how the drive handles long-term workloads.

- Desktop HDD: tuned for general use, good value, often used for media and bulk storage.

- NAS HDD: firmware and vibration features aimed at multi-drive enclosures and steady operation.

- Enterprise HDD: built for 24/7 duty cycles, tighter error recovery behavior, and dense racks.

- External HDD: adds an enclosure and USB bridge; great for portable copies and shelf backups.

- Hybrid Drive (SSHD): combines a hard disk with a small flash cache to speed up repeated reads.

Hard Disk In Modern Systems

SSDs dominate for speed, but HDDs keep a strong role where capacity and cost-per-terabyte decide the outcome. Many setups pair an SSD for the operating system with an HDD for libraries, archives, and backups. That division feels natural: one device for instant access, one for deep storage.

Even with newer storage options, the hard disk remains a practical invention: a compact, reusable machine for keeping huge collections of data safe, organized, and ready whenever you need them.

References Used for This Article

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History — IBM 350 Disk Storage Unit: Documents the first commercial hard disk system and its historical significance.

- IBM Archives — IBM 350 Disk Storage Unit: Provides primary historical details about the RAMAC system and early disk storage design.

- Carnegie Mellon University — Hard Disk Drives: Explains HDD structure, operation principles, and performance characteristics.

- Seagate Technology — What Is a Hard Disk Drive?: Summarizes modern HDD components, recording methods, and use cases.

- USENIX — Disk Drive Performance and Reliability: Analyzes mechanical limits, latency, and reliability factors in disk drives.

- T13 Technical Committee — ATA/ATAPI Command Set: Defines standardized interfaces and behaviors used by SATA hard disk drives.