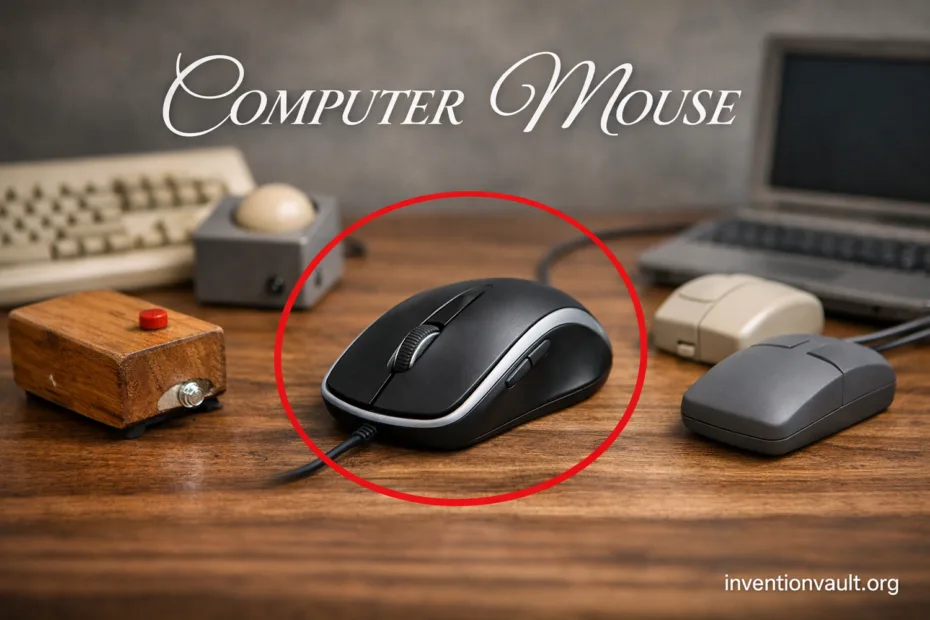

| Invention | Computer Mouse |

| Primary Purpose | Hand-controlled pointing device for moving an on-screen cursor and selecting interface elements |

| Key People | Douglas Engelbart (concept & direction) and Bill English (engineering lead on the first prototype) |

| First Prototype | Built in fall 1964: a wooden shell on two perpendicular wheels with a single button |

| Original Technical Name | “X-Y position indicator” (a practical description of two-axis motion sensing) |

| Patent | US 3,541,541, titled “X-Y position indicator for a display system” (filed 1967, issued 1970) |

| Public Debut | Shown in a landmark 1968 live demonstration of interactive computing, featuring pointing, selection, and on-screen collaboration |

| Early Rolling-Ball Variant | Telefunken Rollkugel (1968): a ball-based design similar in principle to later ball mice |

| Major Tracking Milestones | Optical (1980) work at Xerox PARC; scroll wheel popularized in 1996; laser tracking introduced in consumer mice in 2004 |

| Core Idea | Convert hand motion into precise two-axis signals, then map them to cursor movement and click actions |

A computer mouse looks simple, yet it changed how people think with screens. It turns tiny hand movements into cursor motion, then lets you select, drag, and scroll with buttons and a wheel. That bridge between human motion and digital control is why the mouse stayed relevant through decades of changing computers.

Origins and Early Designs

The earliest mouse was built to answer a practical question: which device lets a person pick things on a screen fast and with few errors? The prototype’s two-wheel approach measured movement along X and Y, then translated it into the on-screen pointer.

Milestones That Shaped The Mouse

- 1964 — First working wooden prototype on perpendicular wheels.

- 1968 — Live public demonstration of interactive screen work using a mouse.

- 1968 — Rolling-ball concept appears commercially (Telefunken Rollkugel).

- 1980 — Optical tracking emerges in research as a practical sensor path.

- 1996 — The scroll wheel becomes mainstream, reshaping navigation.

- 2004 — Consumer laser tracking arrives, improving performance on more surfaces.

How A Computer Mouse Works

Every mouse does the same job: it measures relative movement and sends that motion as digital signals to the computer. The system then applies settings like pointer speed and acceleration to decide how far the cursor travels.

| Step | What Happens |

| 1. Motion Sensing | A sensor detects movement: wheels/ball in older designs, or an optical image sensor in modern ones. |

| 2. Signal Processing | A tiny microcontroller turns sensor data into counts (delta X, delta Y). |

| 3. Data Transfer | Counts travel over USB (wired) or wireless radio/Bluetooth to the host. |

| 4. Cursor Mapping | The operating system maps counts to cursor motion using speed, acceleration, and display scaling. |

| 5. Click and Scroll | Switches register clicks, while the wheel encoder reports scroll steps (and sometimes tilt). |

A small but important detail: most modern sensors are like tiny cameras. They take rapid snapshots of the surface texture, compare frames, and estimate motion. That is teh reason a good mouse can feel stable even at very low hand speed.

Tracking Technologies

Mouse history is a story of tracking. Each generation improved accuracy, reduced maintenance, and worked on more surfaces. Knowing the main types helps you recognize what a device can do, and why it behaves the way it does under a hand.

Wheel And Early Mechanisms

The first mouse used two wheels set at right angles. Each wheel tracked one direction, creating a clean X-Y signal. This design proved the idea, even before the ball era made motion smoother.

Ball Mouse

A ball mouse places a coated ball against rollers inside the shell. As the ball turns, the rollers rotate and generate motion signals. It’s a classic approach, yet dirt and dust can reduce smoothness over time.

Optical LED

An optical mouse shines an LED onto the surface and reads texture changes with an image sensor. This removes the mechanical ball, improving reliability and keeping tracking consistent for most desks and mousepads with normal texture.

Laser

A laser mouse uses laser illumination to reveal finer surface detail. In practice, that often means better tracking on tricky finishes. The result can feel more predictable when a surface is glossy, patterned, or simply unusual compared to a standard pad.

Connection Types

Connection choice changes latency, battery needs, and portability. A wired mouse sends data over a cable and never worries about charging. A wireless mouse trades that cable for radio convenience, while aiming to keep response consistent.

- USB Wired: steady power and simple compatibility, common for desktops and laptops.

- 2.4 GHz Receiver: a small dongle handles the radio link; often chosen for strong responsiveness.

- Bluetooth: pairs directly, reducing ports used; great for travel, with battery life as a common advantage.

- Legacy PS/2: older desktops may still support it; notable for its place in PC history.

Shapes And Subtypes

The word mouse covers several physical subtypes. Shape affects wrist posture, finger reach, and long-session comfort. Subtypes also exist for people who prefer precision, reduced motion, or a stable hand position.

Standard Symmetrical

A symmetrical mouse can suit either hand. It tends to be compact and familiar, making it easy to share. The feel is shaped by button placement and shell height, not only the sensor.

Right-Hand Sculpted

A sculpted mouse supports the palm and guides the thumb. This often reduces grip force during long work sessions. People notice it most when switching back to a flat travel mouse, where the hand must stabilize more actively.

Vertical Mouse

A vertical mouse rotates the hand into a handshake posture. The goal is to reduce forearm twist and keep alignment neutral. It can feel different at first because muscle use shifts while the cursor work stays the same.

Trackball Mouse

A trackball keeps the body still while your fingers roll a ball. Desk movement drops sharply, which can help in tight spaces. It’s also a direct cousin of the older ball mechanism, just flipped for stationary use.

Parts Inside A Modern Mouse

Under the shell, a modern mouse is a compact system: optics, electronics, and mechanics. Each part affects feel. A crisp click comes from switch choice, while tracking stability depends on the sensor and how the lens is aligned.

- Sensor Module: LED/laser illumination, lens, and an imager that measures movement.

- Microcontroller: interprets sensor frames and reports delta X/Y plus button states.

- Primary Switches: left/right click components that shape tactile response.

- Scroll Encoder: converts wheel turns into steps for scrolling (and sometimes tilt).

- Feet: low-friction pads that influence glide and surface feel.

- Battery And Radio (wireless): power control plus a transceiver for stable communication.

Specs That Change Real Use

Spec sheets can look noisy, so it helps to focus on what actually changes the experience. A mouse feels “right” when movement is consistent, clicks are predictable, and scrolling matches reading speed. Three specs show up again and again: sensitivity, polling, and surface behavior.

| Specification | What It Changes |

| DPI/CPI | How far the cursor moves per physical distance; it affects fine control and screen-to-hand feel. |

| Polling Rate | How often reports are sent; it can influence perceived responsiveness, especially on fast pointer movements. |

| Lift-Off Behavior | How the sensor reacts when the mouse is lifted; it affects repositioning without cursor drift. |

| Switch Feel | Click force and feedback; it shapes comfort and consistency for repetitive actions. |

| Wheel Encoder | Scroll steps and smoothness; it changes reading speed and precision in long documents. |

Why The Mouse Stayed Important

Many devices can point at a screen, yet the mouse earned a special role because it supports precise selection with low fatigue. The small motion range, the stable resting position, and the clear click action make it strong for editing text, arranging layouts, and any work where a few pixels matter.

Precision is not only about the sensor. It’s the blend of tracking, stable grip, and predictable feedback that makes a mouse feel trustworthy.

Common Behaviors You Might Notice

Cursor Jitter What It Usually Means

Jitter often points to a surface or sensor mismatch. Some sensors prefer a consistent texture, and reflective finishes can confuse frame comparisons. A mousepad with a steady pattern can restore smooth motion.

Accidental Double Click What It Usually Means

Double-click behavior commonly comes from aging switches or a very sensitive click setting at the system level. Mechanical switches wear gradually, so the change can feel subtle at first, then suddenly obvious.

Scroll Wheel Skips What It Usually Means

Scroll skips are tied to the wheel encoder or debris affecting its readings. Some wheels are tuned for distinct steps, others for smooth travel; both rely on clean, consistent signals.

References Used for This Article

- United States Patent Office — X-Y Position Indicator for a Display System (US 3,541,541): Official patent record documenting the original computer mouse concept and mechanism.

- SRI International — Douglas Engelbart Biography: Overview of Engelbart’s work and his role in interactive computing and input devices.

- Computer History Museum — Engelbart Mouse Prototype: Archival description of the first mouse prototypes and their technical design.

- Xerox PARC Archives — Pointing Device Research: Documentation of optical tracking research that shaped modern mouse technology.

- Telefunken Company Archives — Rollkugel (1968): Corporate archive noting early rolling-ball pointing devices related to mouse evolution.

- IEEE Xplore — Optical Mouse Sensor Design: Technical paper explaining principles behind optical motion sensing in mice.

- USB Implementers Forum — HID Usage Tables: Specification source describing how mouse movements and clicks are reported to computers.