| Invention Name | Abacus |

| What It Is | A manual calculating device that uses movable counters (often beads) to represent place value. |

| Core Principle | Place-value representation plus consistent rules for combining quantities on each rod or line. |

| Inventor | No single inventor. The abacus idea evolved across multiple cultures as counting boards and later as counting frames. |

| Early Forms | Sand or dust counting boards and flat reckoning tables where stones or tokens were moved across marked lines. |

| Earliest Surviving Artifact Often Cited | The Salamis Tablet, a marble counting board dated to around 300 BCE (survival is rare, so earlier everyday tools may not have endured). |

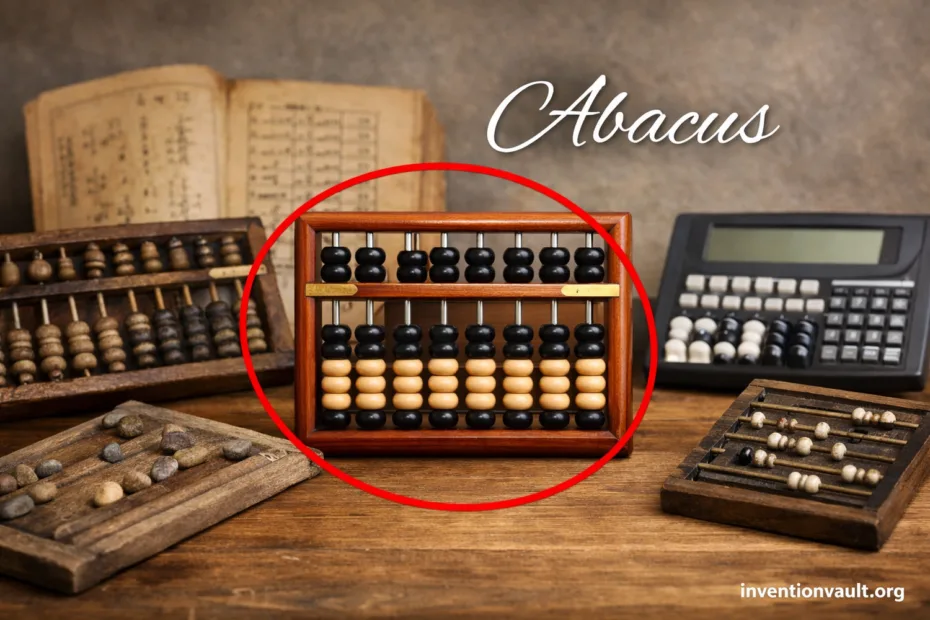

| Classic Families | Counting board (tokens on lines), Roman hand abacus (slotted metal), suanpan (Chinese 2:5), soroban (Japanese 1:4), schoty (Russian bead frame). |

| Number Systems | Most modern forms align with decimal place value; several traditions also support fractions or mixed units with special rows/columns. |

| Why It Matters | A durable, low-tech way to model number structure, sharpen mental calculation, and keep arithmetic transparent. |

An abacus is not a “toy calculator.” It is a physical number system you can see and touch. Each bead movement makes place value visible, which is why this invention stayed useful across trade, schooling, and daily accounting for centuries.

What an Abacus Is

An abacus is a representational tool: it stores numbers in a stable layout, then lets you transform them using simple movement rules. Unlike paper arithmetic, the abacus keeps quantity and position tied together so you can “read” a value at a glance.

A Simple Definition That Holds Up

Think of it as a place-value machine with no electricity. Each rod or row stands for a digit position (ones, tens, hundreds), and the beads are units you can gather or release. The design stays recognizable even when the bead layout changes between traditions.

Core Parts and Place Value

- Frame: the rigid body that keeps everything aligned; a steady frame makes reading cleaner.

- Rods or Wires: each rod is one place; more rods means a wider number range.

- Beads: the movable counters; their positions store value in a consistent way.

- Reckoning Bar (on many Asian types): beads touching the bar are active; this makes state unambiguous.

The clever part is how the abacus pairs a digit column with a small set of bead values. This lets the same physical layout express huge numbers with tidy repetition. Once you grasp place value, the device becomes surprisingly fast.

| Style | Upper Section | Lower Section | Typical Encoding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suanpan (Chinese) | Usually 2 beads, each worth 5 | Usually 5 beads, each worth 1 | Bi-quinary (5s + 1s) with extra flexibility for older methods |

| Soroban (Japanese) | 1 bead, worth 5 | 4 beads, each worth 1 | Streamlined decimal place-value layout |

| Schoty (Russian) | Usually no split bar | Often 10 beads per wire (with visual separators on some wires) | Row-based decimal counting; the feel is direct and rhythmic |

How Beads Encode Numbers

Many abaci mark a clean boundary between inactive and active beads. On a soroban or suanpan, beads pushed to the reckoning bar count; beads away from it do not. That simple rule keeps the state of each digit crystal-clear, even when hands move quickly.

This “one-column logic” scales beautifully. Put columns side by side and you get a complete base-10 representation. The abacus is compact because each column needs only a few beads to express 0 through 9, which is why the device stayed practical for commerce and teaching for so long.

The abacus turns arithmetic into visible structure, not hidden steps.

Origins and Early Evidence

The earliest “abacus” was likely a board where dust or sand could be smoothed and re-marked, making calculation easy to reset. Even the word abacus is often linked to ideas of sand and wiping, echoing that erasable surface.

Physical survival is the tricky part: everyday tools wear out. Still, a famous surviving piece is the Salamis Tablet (around 300 BCE), a marked marble slab associated with counter-based calculation. It shows how a lined surface can support large-number work without modern numerals.

Counting Boards

A counting board uses lines and tokens. The lines act as place markers, while pebbles or discs are the units.

Roman Hand Abacus

Romans used a compact slotted device with sliding beads in grooves. It reflects bi-quinary thinking (5s and 1s) and even includes fraction support on some reconstructions.

Major Abacus Traditions

Across regions, abaci share the same backbone: a stable layout for digits and a small set of bead values that repeat by column. The differences are not cosmetic; they shape how the tool feels in the hand and how quickly a user can scan and verify a number.

Suanpan

- Decks: often 2 beads above, 5 below; a 2:5 layout.

- Strength: flexible representation, including room for older calculation conventions.

- Context: documented in China by the Han era; later became central to commercial arithmetic.

Soroban

- Decks: 1 bead above, 4 below; the familiar 1:4 format.

- Design goal: a cleaner decimal layout with fewer beads to read.

- History: derived from the suanpan after its introduction to Japan; the modern layout took shape through refinement over time.

Schoty

- Rows: often 10 beads per wire; some rows include color markers for quick grouping.

- Feel: fast, sweeping bead motion supports rhythm and consistency.

- Everyday use: long associated with shop and office calculation, where speed and repeatability mattered.

Design Variations You Might See

Not every abacus is built for the same environment. Some emphasize training, others aim for durability in busy workplaces. These variations change how easily you can read a value and how reliably beads return to a resting position.

- Rod count: educational frames often use 13, 17, or 23 rods so learners can see longer numbers without crowding. More rods expand range.

- Bead shape: rounded beads glide smoothly; flatter beads can “lock” into place, supporting stability.

- Decimal markers: some frames add a visual cue for the decimal point so reading is instant.

- Materials: hardwood looks classic; plastic is consistent and resilient. Either can be excellent when tolerances are tight.

What the Abacus Can Do

At its core, the abacus supports the same arithmetic goals you expect from written work: addition, subtraction, and—through established methods—multiplication and division. The difference is that each step leaves a visible trace on the beads, so checking work feels more like inspection than re-doing.

Why It Feels Fast

- Low friction: bead motion is immediate; no writing overhead, no erasing, no page turning.

- Chunking: the 5-and-1 structure groups quantity naturally, giving pattern to digits.

- Error spotting: a “wrong-looking” column stands out because the layout has a normal shape.

One small detail that surprises many readers: a skilled user often experiences the abacus as a steady rhythm. That rhythm helps keep operations organized, even when numbers get large. It’s not magic—just a tool that makes structure obvious, bead by bead. And yes, sometimes teh simplest designs last the longest.

Modern Use and Lasting Value

Today, the abacus remains a practical way to build number sense because it ties each digit to a physical state. In classrooms, it supports place-value understanding. In cultural settings, it preserves a craft tradition. In everyday life, it stays useful anywhere a reliable, battery-free calculator matters.

Care, Materials, and Longevity

A well-made abacus is built for repeated motion. Smooth rods, consistent bead sizing, and a frame that stays square protect accuracy over time. Wooden frames benefit from a stable environment; plastic frames handle travel well. Either way, a clean surface and gentle handling preserve the glide that makes the tool feel effortless.

References Used for This Article

- The British Museum — Salamis Tablet: An official museum record describing the marble counting board often cited as early physical evidence of abacus-style calculation.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art — Abacus (Counting Frame): A curatorial description of an abacus artifact explaining structure, materials, and historical use.

- Smithsonian Institution — Abacus: An institutional overview outlining how abaci encode numbers and why they mattered in trade and education.

- University of St Andrews — History of the Abacus: An academic summary tracing the development of counting boards and bead frames across cultures.

- National Museum of the United States Air Force — Abacus: A concise institutional explanation of the abacus as a manual calculating device with place-value logic.

- Victoria and Albert Museum — Abacus: A museum catalog entry documenting an abacus object and its functional design.