| Detail | Verified Information |

|---|---|

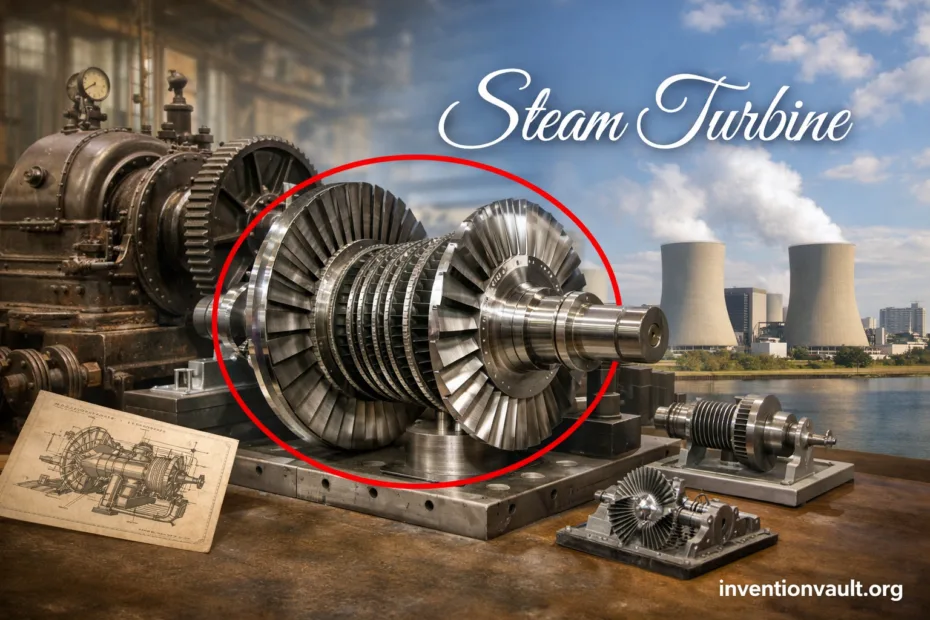

| Invention | Steam turbine (a rotating turbomachine driven by expanding steam). |

| What It Converts | Steam pressure and temperature (enthalpy) into continuous rotary shaft power. |

| Modern Breakthrough Era | Late 19th century, when multi-stage designs made turbines practical at useful power levels. |

| Key Pioneer | Sir Charles A. Parsons — early patents and a historic turbo-generator in 1884. |

| Key Pioneer | Gustaf de Laval — patent for a steam-driven turbine motor dated September 25, 1883 (filed July 28, 1883). |

| Another Major Line | Charles G. Curtis — velocity-compounded impulse concepts reflected in a patent dated September 7, 1897 (filed August 4, 1896). |

| Iconic Demonstrator | Turbinia — launched in 1894, widely described as the first ship powered by steam turbines. |

| Core Design Families | Impulse (jets/nozzles drive blades), reaction (pressure drop shared across fixed and moving blades), and staged hybrids. |

| Why It Mattered | High-speed, scalable rotary power that paired naturally with electric generators and large industrial drives. |

The steam turbine is one of the rare inventions that changed not just a machine, but an entire infrastructure of power. Instead of pushing pistons back and forth, it turns heat into smooth rotation—quietly, continuously, and at scales that made modern electricity systems practical. Its “invention” is best understood as a focused leap in the 1880s and 1890s, when a few bold designs proved that steam could drive blades efficiently enough to outperform earlier approaches.

What a Steam Turbine Is

A steam turbine is a rotating engine where steam expands through shaped passages and transfers energy to a bladed rotor. The flow is continuous. That single trait—continuous flow—unlocks a different performance ceiling than piston engines, which deliver power in pulses. In turbines, steam energy becomes shaft rotation through two linked effects: momentum change (steam direction and speed change across blades) and controlled pressure drop across stages.

The Two Core Elements

- Fixed blades / nozzles (stator): shape the flow and often perform a controlled expansion of steam, converting pressure into velocity.

- Moving blades (rotor): capture that flow and convert it into torque on the shaft, with blade geometry tuned to the intended speed and pressure range.

Why Steam Turbines Became a Breakthrough Invention

The pivotal advantage was not a single clever blade. It was the system-level fit: turbines deliver steady, high-speed rotation that matches the needs of generators and large rotating machinery. Once engineers learned how to split the steam’s energy across multiple stages, turbines scaled rapidly.

- Scalability: multi-stage layouts made it possible to grow from small experimental units to large industrial machines.

- Smoother rotation: less cyclical vibration compared with reciprocating motion, especially valuable at higher power levels.

- Higher practical speeds: turbines naturally run fast; coupling that speed to generators changed what “central power” could look like.

- Efficiency pathways: staging, improved nozzles, better seals, and condensing arrangements pushed performance upward over time.

From Early Ideas to Practical Steam Turbines

Long before the turbine became a practical prime mover, inventors knew steam could create rotation. The hard part was not “making something spin,” but extracting enough energy efficiently, controlling the flow, and turning very high rotor speed into usable output without destructive vibration or losses. The late 19th century delivered the missing pieces.

Gustaf de Laval and the High-Speed Path

De Laval’s early work emphasized speed. His U.S. patent dated September 25, 1883 describes a steam-driven turbine motor concept and shows how tightly mechanical output and flow design were linked even at this early stage. High rotational speed made turbines attractive, yet it also created a new engineering challenge: turning that speed into practical shaft work without excessive loss.

- 1883 patent milestone: a documented step in turbine motors for steam and other motive fluids.

- Nozzle and jet thinking: accelerating steam before it meets blades became central to impulse practice.

- Speed management: gearing and mechanical arrangement became as important as blade shape.

Charles Parsons and Multi-Stage Reaction Turbines

Parsons recognized the power of staging: taking the steam’s energy in smaller steps rather than trying to extract it all at once. A 1936 Nature article notes that Parsons took out early patents in 1884 and built a “historic little turbo-generator” preserved in the Science Museum. That combination—patentable principle plus working hardware—marks the steam turbine’s shift from concept to industrial promise.

- Reaction-stage principle: pressure drop and energy release occur in both fixed and moving blade passages.

- Practical scaling: many stages allowed efficiency and output to rise together.

- Turbogenerator fit: rotary motion aligned naturally with electrical generation.

What made the invention “stick” was not rotation itself, but a reliable way to stage expansion and capture energy repeatedly without losing control of speed, leakage, or blade stress.

Key Moments That Established Steam Turbines

Once the core designs worked, steam turbines advanced through visible demonstrations and rapidly multiplying applications. Several milestones became reference points for engineers and manufacturers.

| Year | Milestone | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| 1883 | De Laval patent dated Sept. 25, 1883 (filed July 28, 1883). | A clearly documented turbine-motor step in the modern invention era. |

| 1884 | Parsons’ early patents and a preserved turbo-generator. | Multi-stage thinking turns turbines into scalable machines. |

| 1894 | Turbinia launched as a steam-turbine-driven ship. | A compelling real-world platform for turbine propulsion. |

| 1897 | Curtis patent dated Sept. 7, 1897 (filed Aug. 4, 1896). | Velocity-compounded impulse ideas broaden practical turbine layouts. |

| 1890s | Rateau develops multistage impulse approaches. | Pressure staging reduces stage count for a given duty and shapes later practice. |

Turbinia and Public Proof

Turbinia is widely presented as the world’s first steam-turbine-powered ship, launched in 1894. Its well-documented public demonstration in 1897 gave turbine propulsion a credibility that drawings and prototypes could not. Even readers focused on electricity generation can learn from this: turbines gained momentum when they proved dependable under demanding operating conditions.

Curtis, Compounding, and a New Impulse Toolbox

Impulse turbines extract energy from high-speed jets striking moving blades. Curtis expanded the impulse family by using velocity compounding—spreading the jet’s work across multiple moving rows with intermediate fixed rows. A patent dated September 7, 1897 (filed August 4, 1896) reflects this direction. Compounding offered a practical way to manage high velocities without forcing a single rotor row to do everything.

Rateau and Pressure Staging

Pressure staging takes a large overall pressure drop and divides it into multiple steps, often reducing the number of stages needed compared with very fine-grained arrangements. Auguste Rateau is credited with developing a multistage impulse approach that influenced the way steam expansion was distributed across a turbine’s length. This helped designers balance efficiency, size, and mechanical simplicity.

Impulse and Reaction: The Defining Design Split

Many turbine details vary by manufacturer and era, yet one distinction keeps reappearing because it shapes everything else: where the pressure drop happens. The terms “impulse” and “reaction” describe that choice.

| Design Family | Where Steam Expands Most | Signature Strength | Classic Names |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impulse | Primarily in fixed nozzles; rotor mainly changes momentum. | Clear jet control and strong performance at high pressure drops per stage. | De Laval, Curtis, Rateau |

| Reaction | Across both stator and rotor blade passages. | High efficiency across many stages with smooth flow turning. | Parsons |

How a Steam Turbine Stage Works

A “stage” is a repeating unit where steam is guided, expanded, and redirected so that the rotor can take another measured slice of energy. In multi-stage turbines, the stages form a controlled descent from high pressure to low pressure. This staged approach is the heart of the invention’s practical success.

Typical Stage Components

- Stator passages: guide steam, often accelerating it.

- Rotor blades: convert flow energy into torque.

- Seals: limit leakage that would bypass blades.

- Bearings: support the rotor and manage axial/radial loads.

- Control valves: regulate flow and output without destabilizing the machine.

Why Staging Matters

- Efficiency: small pressure drops per stage reduce avoidable losses.

- Blade loading: spreading work avoids overstressing a single row.

- Speed control: staged extraction helps keep rotor speed within workable limits.

- Scalability: more stages can mean more power without redesigning the basic physics.

A Clear Visual Explanation

Engineering Advances That Made Steam Turbines Dominant

After the initial invention era, progress came through refinements that protected efficiency and reliability as machines grew larger. Many of these are invisible in a simple “who invented it” story, yet they explain why the steam turbine became a platform technology.

- Convergent-divergent nozzles: improved conversion of pressure into high-velocity flow for impulse practice.

- Better blade profiles: reduced losses from separation and shock, especially across changing pressures.

- Sealing and clearances: small leakage paths matter enormously when stages multiply.

- Balancing and vibration control: high rotational speed demands careful mass distribution and stable bearings.

- Condensing arrangements: lowering exhaust pressure increases the energy a turbine can extract from steam.

- Compounding and staging strategies: velocity compounding (Curtis) and pressure staging (Rateau) offered alternative routes to practicality.

Major Steam Turbine Variants

Steam turbines are not a single shape. They are a family of solutions built around the same conversion principle. The variants below appear repeatedly because each solves a specific engineering trade-off.

Axial-Flow Turbines

Steam flows roughly parallel to the shaft through a sequence of stages. This layout suits large power levels and is the common backbone of modern power-generation machines.

Radial-Flow Turbines

Flow moves inward or outward across the radius. These can appear in specialized arrangements where compactness and stage design constraints favor radial geometry.

Condensing and Back-Pressure

Condensing units aim for low exhaust pressure for higher energy extraction, while back-pressure units exhaust at useful pressure for heating or process duties in industrial systems.

How the Invention Shaped Modern Power Systems

Steam turbines became the primary prime movers in large power stations as machine size climbed. A widely cited historical note is that by around 1900 turbine-generator units had reached the kilowatt scale, and within a decade outputs had grown dramatically—an increase that made centralized generation practical at levels piston engines struggled to match. The turbine’s success came from a blend of thermodynamics and manufacturable mechanics: many stages, precise blades, and a rotor that could run continuously for long periods.

Where Steam Turbines Commonly Appear

- Utility-scale electricity generation: turbines coupled to synchronous generators at standardized speeds.

- Industrial power and process plants: turbines used for mechanical drives and combined heat-and-power arrangements.

- Marine propulsion history: early demonstration platforms proved rotary propulsion at high speed and reliability.

- Geothermal and waste-heat recovery: where steam or vapor expansion can be harvested for power.

Key Terms That Appear in Steam Turbine History

| Term | Meaning in Plain Language | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Stage | A repeating stator-rotor unit that extracts part of the steam’s energy. | Staging is the practical foundation of large turbines. |

| Compounding | Spreading work across multiple blade rows to manage velocity or pressure changes. | It makes high-energy steam jets easier to use efficiently. |

| Impulse | Steam expands mainly in nozzles; blades take energy from jet momentum. | Central to de Laval, Curtis, and many staged designs. |

| Reaction | Steam expands across both fixed and moving passages. | Defines the Parsons tradition and many high-efficiency layouts. |

| Condenser | Equipment that lowers exhaust pressure by condensing steam into water. | Lower back pressure increases energy extraction potential. |

References Used for This Article

- Science Museum Group Collection — Parsons’ steam turbine generator, 1884: Museum record describing the preserved early turbo-generator associated with Parsons’ 1884 work.

- Nature — The Development of the Parsons Steam Turbine: A historical article (published 1936) discussing Parsons’ 1884 patents and early turbo-generator.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica — History of steam turbine technology: Overview of modern steam turbine development and key contributors across the late 19th century.

- United States Patent (via Google Patents) — US285584A, Turbine for Steam and Other Motive Power: Primary patent text showing the 1883 date and filing details for de Laval’s turbine-motor concept.

- Discovery Museum — Turbinia: Museum page documenting Turbinia’s 1894 launch and its role in demonstrating steam turbine propulsion.

- ASME — The First 500-Kilowatt Curtis Vertical Steam Turbine (PDF): Engineering landmark document summarizing early commercial Curtis turbine developments.

- United States Patent (via Google Patents) — US589466A, Elastic-Fluid Turbine: Primary patent record showing Curtis’ 1896 filing and the 1897 patent date for an elastic-fluid turbine.

- Deutsches Museum Digital Library — Rateau, Auguste Camille Edmond: Biographical reference noting Rateau’s contributions to multistage impulse turbine development.