| Detail | Information |

|---|---|

| What This Invention Is | A human-made satellite that carries global signals from orbit to receivers on Earth. |

| Main Idea | Place a radio relay (or a precision timing beacon) above Earth so signals can travel farther, reach wider areas, and keep stable coverage. |

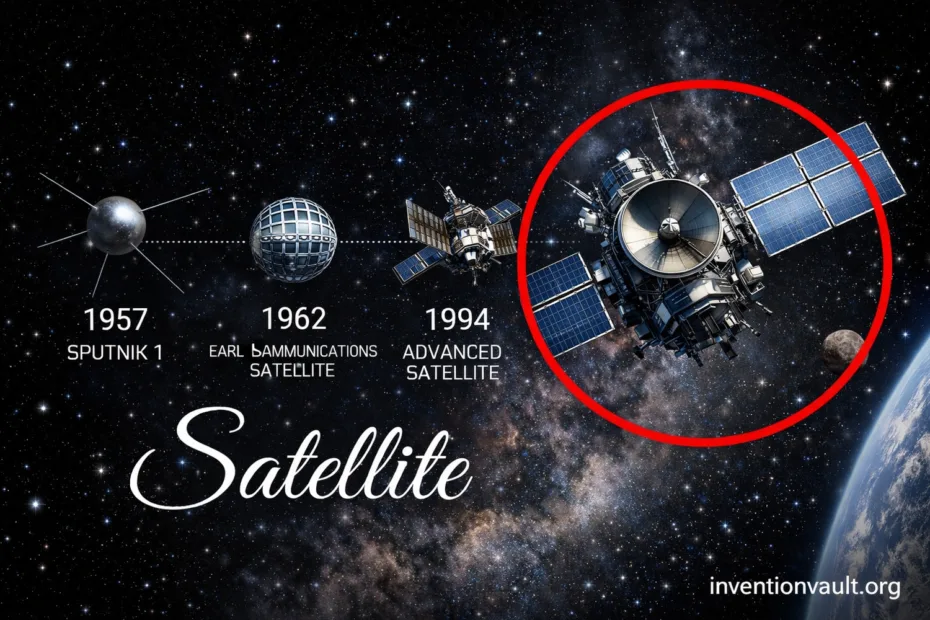

| Earliest Widely Recognized Milestone | Sputnik 1 (first artificial Earth satellite), launched October 4, 1957, proved that orbiting transmitters could broadcast detectable signals worldwide. |

| Key Concept That Shaped Modern Services | Geostationary and geosynchronous orbits enabled “fixed-in-the-sky” style links for telecom and broadcast, while LEO/MEO enabled fast coverage and navigation. |

| Signal Types Carried | Communication (voice, data, internet), navigation and timing (GNSS), Earth observation data, weather imagery, scientific measurements. |

| Typical Orbits Used | LEO (roughly 160–2,000 km), MEO (about 2,000–35,786 km), GEO (near 35,786 km above the equator), plus polar, sun-synchronous, and highly elliptical paths. |

| Core Hardware | Payload (transponders, antennas, sensors), bus (power, thermal control, attitude control), command links, and ground stations that manage the full system. |

| Power Breakthrough | Early solar-powered satellites demonstrated that solar cells could run spacecraft systems for long durations. |

| Why It Matters Today | It underpins global connectivity, precise time, positioning, and Earth monitoring that supports daily life and long-term planning. |

A satellite is more than a machine in space. It is a moving platform that carries signals across oceans, deserts, and mountains, often in a single hop. When you think “global signals from orbit,” think of a system built for reach, timing, and reliability—and built to work quietly, day after day.

How Orbital Signals Work

Most satellite signals follow a simple path: a ground transmitter sends an uplink, the satellite receives it, then sends a downlink to another place on Earth. That “receive-and-send” step can be a classic transponder (often called a bent-pipe relay), or it can include onboard processing in newer designs.

- Uplink: A ground station aims a radio beam toward the satellite. The transmitter uses carefully chosen frequencies and power.

- Payload action: The satellite filters, amplifies, and may shift the frequency to reduce interference. The payload does the heavy lifting.

- Downlink: The satellite sends a controlled signal back to Earth. Receivers decode the data or the timing marks.

Navigation systems add an important twist: the satellite broadcasts a time-stamped signal tied to atomic clock references. Your receiver compares arrival times from multiple satellites and solves for position, time, and clock offset. It feels simple in your hand, but the math is doing serious work.

Origins and Early Milestones

The story of the modern satellite blends theory, rocket engineering, and practical communications needs. In 1945, Arthur C. Clarke described how satellites in a high, Earth-matching orbit could provide wide radio coverage. It wasn’t a product pitch; it was a blueprint for a new kind of infrastructure.

Then came the turning point: Sputnik 1 in 1957. Its radio beeps were simple, yet they proved something huge—an object could stay in orbit and broadcast a recognizable signal across the planet. That proof unlocked everything that followed.

| Milestone | Why It Mattered |

|---|---|

| 1957 — Sputnik 1 | First artificial satellite; validated orbital broadcasting and tracking. |

| 1962 — Telstar 1 | Early active communications; relayed TV and telecom across large distances. |

| 1963 — Syncom 2 | First successful geosynchronous communications satellite; a key step toward fixed coverage. |

| 1964 — Syncom 3 | First geostationary communications satellite; enabled steady links from a near-fixed sky position. |

| 1965 — Intelsat 1 (Early Bird) | First commercial geosynchronous comm satellite; helped normalize “live via satellite.” |

| 1978 — Navstar 1 | Early GPS-era navigation satellites; sharpened the role of timing signals. |

Energy mattered too. Early spacecraft showed that solar power could keep a satellite running long after chemical batteries would quit. That shift made long-life services realistic, from weather imaging to steady communications. The modern signal economy depends on that quiet power source.

Orbits That Shape Coverage

Orbit is not decoration. Orbit is the service design. It sets latency, coverage, and how often a satellite can “see” a given place. Choose the orbit, and you choose the user experience.

| Orbit Type | Typical Role | Practical Effect |

|---|---|---|

| LEO | Broadband constellations, Earth observation, some science | Lower delay, smaller coverage per satellite, needs many satellites for global reach. |

| MEO | Navigation and timing (GNSS) | Wide coverage with fewer satellites than LEO; stable geometry for positioning. |

| GEO | TV, fixed satellite services, weather imaging | One satellite covers a very large region; higher delay but steady sky position. |

| Polar / Sun-Synchronous | Mapping, environmental monitoring | Consistent lighting for imaging; repeatable passes enable long-term comparison. |

| Highly Elliptical | High-latitude coverage | Long “hang time” over certain regions; useful where GEO looks low on the horizon. |

Satellite Types That Deliver Global Signals

Communications Satellites

A communications satellite is a managed relay in space. Some operate as classic transponders, others route traffic onboard. The goal stays constant: deliver reliable links across long distances, even where cables are impractical.

- Fixed services: Stable dishes point to a GEO satellite for consistent bandwidth and predictable coverage.

- Mobile services: Ships, aircraft, and remote users rely on beam management and robust coding to keep the link clean.

- LEO broadband: Many satellites share the load, handing connections off from one craft to the next to keep users online.

Navigation and Timing Satellites

Global navigation is powered by signals plus time. Each satellite continuously broadcasts a message that includes precise timing and orbit data. Your receiver measures tiny differences in arrival time. With enough satellites in view, it solves for a stable position fix and a corrected clock.

This is why the word timing keeps showing up. Telecom networks, financial timestamping, and power grids often depend on satellite-derived time. If you want global coordination, you need teh same beat everywhere.

Weather and Earth Observation Satellites

Weather satellites and imaging missions turn orbit into a viewpoint you can trust. In GEO, a satellite watches the same region continuously, supporting frequent updates. In polar and sun-synchronous orbits, satellites map the full globe with repeatable geometry, making long-term comparisons meaningful.

- Geostationary weather imaging: Frequent snapshots of cloud motion and storm structure over wide areas.

- Earth observation: Multispectral sensors detect patterns in vegetation, water, and land features with consistent repeat visits.

- Radar imaging (SAR): Active sensing that can operate through clouds and at night, depending on mission design.

Inside a Satellite: Bus and Payload

A working satellite is a balance between precision and survivability. It must point antennas accurately, stay within temperature limits, and manage power while passing in and out of sunlight. The payload earns the mission; the bus keeps it alive.

Payload Elements

- Antennas that shape beams and concentrate energy where it’s needed.

- Transponders and amplifiers that preserve signal quality.

- Sensors (for observation missions) tuned to specific wavelengths or radar bands.

- Onboard processing that can route data, compress imagery, or manage flexible channels.

Bus Elements

- Power: solar arrays plus batteries for eclipse periods.

- Attitude control: wheels, sensors, and control logic to keep pointing stable.

- Thermal control: coatings, radiators, and heaters to manage extremes.

- Propulsion: orbit raising, stationkeeping, and safe end-of-life maneuvers.

Ground Systems That Make Space Useful

Satellites do not run themselves. A complete global signals service includes mission control, tracking networks, user terminals, and data processing pipelines. The strongest spacecraft still depends on a strong ground segment.

Three Layers of the System

- Control: Commands, health monitoring, and careful scheduling keep the satellite stable.

- Connectivity: Gateways and teleport facilities link space to fiber networks and data centers.

- Users: From compact receivers to fixed dishes, terminals translate space signals into usable service.

Frequency Bands and What They Enable

Satellites share the radio spectrum with many other services, so band choices matter. Lower bands tend to travel through weather more easily, while higher bands can carry more data but may need smarter link design. A good system matches band to mission.

| Band | Approx. Range | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|

| –L– | 1–2 GHz | Navigation, mobile satellite links, resilient messaging. |

| –S– | 2–4 GHz | Telemetry, tracking, command, some communications. |

| –C– | 4–8 GHz | Reliable links in challenging weather; broadcast and fixed services in many regions. |

| –Ku– | 12–18 GHz | Satellite TV, VSAT networks, many broadband services. |

| –Ka– | 26.5–40 GHz | High-throughput broadband, spot-beam capacity, advanced gateways. |

These ranges are a map, not a promise. Real systems also depend on licensing, regional allocations, antenna size, coding, and local weather patterns. Still, the trade is consistent: capacity versus robustness.

Miniaturization: From Large Platforms to SmallSats

As electronics improved, satellites shrank. Small satellites lowered cost, shortened schedules, and made experimentation more common. A major step was the CubeSat standard (proposed in 1999), which gave teams a shared size and deployment model. That shared standard helped turn small missions into repeatable engineering.

- Why small works: Faster development cycles, focused payloads, and easier rideshare options.

- What still stays hard: Power, thermal control, and antenna performance—physics does not negotiate.

- What it unlocks: More frequent updates, denser coverage, and new approaches to global signals.

What Makes “Global” Possible

“Global” is not one feature. It’s the combined effect of coverage design, signal planning, and operational discipline. Some systems aim for continuous global visibility. Others prioritize specific regions but still rely on orbital motion to reach wide areas over time.

| Design Choice | What It Changes |

|---|---|

| Constellation size | More satellites can mean stronger availability and smoother handoffs. |

| Orbit altitude | Lower altitude can reduce latency; higher altitude can widen coverage. |

| Beam strategy | Spot beams can increase capacity; wide beams can simplify coverage. |

| Frequency selection | Shapes link resilience and throughput, especially in varying weather. |

| Ground network density | More gateways can improve routing options and reduce congestion. |

Operational Care and Long Service Life

Modern satellite systems are managed with a strong focus on reliability and predictability. Operators schedule stationkeeping, monitor component health, and plan end-of-life steps so orbital resources remain useful for future missions. When service is steady, users rarely notice anything—and that is the point.

Seen as an invention, the satellite is a platform. Seen as infrastructure, it is a living network. Either way, it has one defining talent: it turns orbital motion into usable signals that can reach almost anywhere on Earth.

References Used for This Article

- NASA — Sputnik 1: Confirms the 1957 launch milestone and why Sputnik’s signals mattered globally.

- NASA History — Telstar Opened Era of Global Satellite Television: Summarizes Telstar 1’s 1962 role in relaying long-distance television and telecom signals.

- NASA NTRS — Telstar I, Volume 1 (NASA SP-32): Provides authoritative technical documentation on early active communications satellite work.

- NASA/JPL — Earth Science Firsts Timeline: Supports key early milestones including geosynchronous and geostationary satellite “firsts.”

- NOAA OSPO — Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES): Explains why geosynchronous orbit enables continuous regional weather monitoring.

- U.S. Space Force — Global Positioning System: Describes how GPS satellites broadcast navigation signals used to compute time and position.

- GPS.gov (Archived) — Space Segment – GPS: The Global Positioning System: Details the GPS constellation concept and continuous radio-signal broadcasting to users.

- The CubeSat Program (Cal Poly) — CubeSat Design Specification (CDS): Documents the CubeSat standard’s origins and the engineering constraints behind small satellites.

- U.S. FCC — FCC 20-66 (Ku-band and Ka-band definitions): Defines commonly used Ku/Ka satellite frequency ranges in a regulatory context.

- European Space Agency — Satellite Frequency Bands: Gives a clear institutional overview of major satcom bands and typical uses.