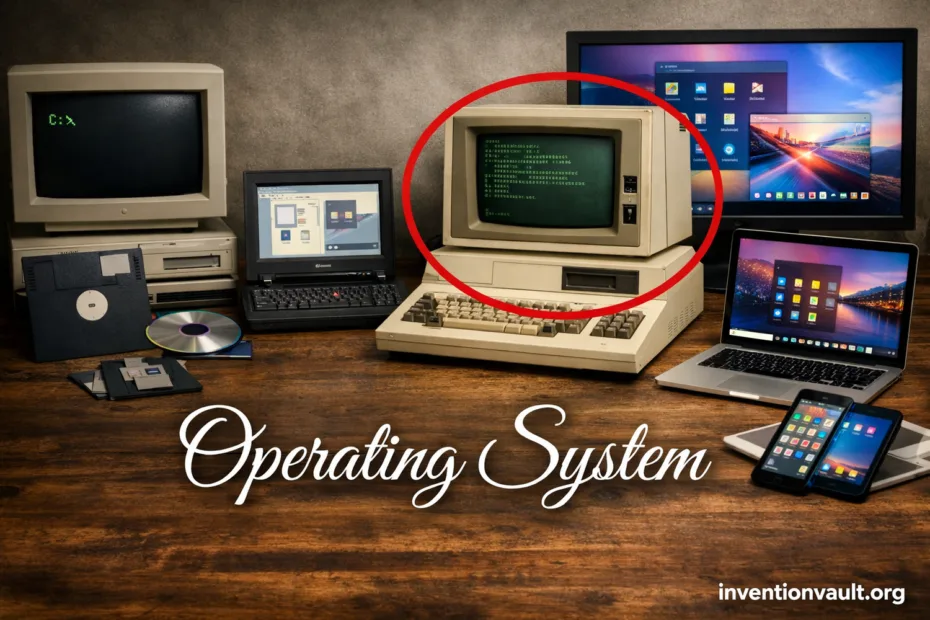

| Invention / Concept | Operating System (system software that manages hardware and runs programs) |

| Core Purpose | Resource control, safe sharing, and reliable execution of applications |

| Often Cited Early OS | GM-NAA I/O for the IBM 704 (mid-1950s, often dated to 1956) |

| Why It Emerged | Manual machine operation was slow; teams needed batch processing and repeatable job control |

| Key Early Ideas | Job scheduling, device management, shared libraries, and accounting for compute time |

| Major Milestones | CTSS (early time-sharing, 1961); OS/360 (large-scale system family, 1964); UNIX (portable multiuser design, 1969); Linux kernel (1991) |

| What “OS” Includes | Kernel, drivers, file system, system libraries, and user interfaces (text and/or graphical) |

| Where You Find It | Servers, desktops, phones, vehicles, appliances, and industrial controllers |

| Common OS “Families” Today | Desktop, server, mobile, embedded, and real-time |

| Typical Design Goal | Balance between speed, stability, and security |

An operating system is the quiet coordinator that lets software and hardware work together without constant human intervention. It decides who gets the CPU, where data lives on storage, and how programs share memory without stepping on each other.

What an Operating System Controls

- CPU time for each process and thread

- Memory allocation, protection, and virtual memory

- Files and folders, plus permissions

- Devices through drivers and interrupts

- Networking via protocol stacks and firewall hooks

- User access with accounts and policy rules

The Practical Result

When an OS is doing its job, you feel smoothness and predictability, not the machinery underneath. Apps open, files save, audio plays, and devices respond because the OS keeps the system state consistent.

Inside the OS

Kernel

The kernel is the core authority. It enforces memory protection, schedules the CPU, and speaks to hardware through drivers.

- Scheduler (who runs next)

- Memory manager (who owns which pages)

- I/O subsystem (disks, network, sensors)

System Services

These are the background helpers that make the system feel complete: logging, updates, and network services. They also keep the enviroment stable when apps misbehave.

- Service daemons (always-on tasks)

- Security agents (policy enforcement)

- Device discovery (plug-and-play)

Interfaces

Interfaces translate intent into action. A shell accepts commands; a GUI offers windows, menus, and touch.

- System calls (API into the kernel)

- CLI tools (scriptable control)

- Desktop / mobile UI (human-friendly workflows)

How Operating Systems Evolved

| Era | What Changed | Why It Mattered |

|---|---|---|

| 1950s batch systems | Job queues and device control | Less idle time, more repeatable runs |

| 1960s time-sharing | Multiple users on one machine, interactive terminals | Computing became conversational, not just scheduled |

| 1970s portability | Portable OS design and high-level languages | Systems could move across hardware with less rewriting |

| 1980s–1990s personal computing | GUI, networking, and multiuser security | Everyday workflows became visual and connected |

| 2000s–today mobile + cloud | App sandboxing, power management, virtualization | Always-on devices and scalable services became normal |

An OS is not “just software.” It is an operating agreement between apps and hardware, enforced by rules that keep the system fair and safe.

Major Types of Operating Systems

| Type | Built For | Typical Priorities |

|---|---|---|

| Desktop OS | Personal work + interactive UI | Responsiveness, driver breadth, app compatibility |

| Server OS | Services + many clients | Stability, security controls, automation |

| Mobile OS | Touch devices + battery limits | Power management, sandboxing, fast updates |

| Embedded OS | Dedicated devices with tight resources | Small footprint, predictable I/O, long support |

| Real-Time OS | Time-critical control (deadlines) | Determinism, bounded latency, priority guarantees |

| Network / Distributed OS | Multiple machines as one system | Coordination, transparency, fault tolerance |

| Hypervisor (OS-adjacent) | Virtual machines with isolation | Strong separation, efficient scheduling, resource quotas |

Kernel Designs and Tradeoffs

Most OS debates land on the kernel. Some designs favor speed, some favor isolation. The “right” shape depends on goals like hardware variety, reliability, and how much complexity you want inside the kernel.

| Kernel Style | What It Means | Common Strength | Common Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monolithic | Many core services run in kernel space together | Performance and direct hardware access | Bugs can have wide impact |

| Microkernel | Kernel stays small; services run in user space via messages | Isolation and fault containment | Messaging overhead and engineering complexity |

| Hybrid | Mix of both: a small core with selected services kept close for speed | Balanced behavior with practical performance | Boundary choices can get messy |

| Exokernel (research) | Kernel exposes hardware safely; libraries build higher-level services | Flexibility and custom control | Hard to standardize and adopt broadly |

Processes, Threads, and Scheduling

A process is a running program with its own address space. A thread is a smaller path of execution inside that process, sharing memory with sibling threads.

| What the OS Schedules | Runnable threads (often) and sometimes process groups |

| What “Context Switch” Means | Saving one task’s state and restoring another’s state so the CPU can continue smoothly elsewhere |

| What Good Scheduling Feels Like | Responsive input, fair sharing, and steady throughput |

Schedulers come in many forms, yet they often revolve around priorities, time slices, and fairness. Some workloads want maximum throughput; others demand instant interaction. A real-time system adds a stricter promise: tasks must run before a deadline, not just “soon.”

Memory Protection and Virtual Memory

Modern OS design leans on memory protection. Each process gets a private view of memory, and the OS enforces that boundary using hardware support and page tables. That separation is a major reason one crashing app doesn’t take everything down.

Virtual Memory App sees: 0x0000 ... 0xFFFF (clean, continuous view) OS maps to: RAM pages + disk-backed pages (when needed) Guardrails: permissions per page (read / write / execute)

Virtual memory also enables safe sharing. Shared libraries can be mapped into many processes, while still keeping private data private. It’s elegant and a little invisible, which is exactly the point for system stability.

File Systems and Data Integrity

A file system is the OS’s long-term memory. It organizes data into names and directories, enforces permissions, and tries hard to keep content consistent when power is lost or a drive behaves strangely.

- Metadata: names, timestamps, and ownership

- Journaling: tracks changes so recovery is cleaner and faster

- Access control: who can read, write, or execute

- Snapshots (in some systems): point-in-time views for rollback

What “Permissions” Usually Mean

Most systems express permissions as read, write, and execute rights tied to a user and group. This simple model scales surprisingly well from laptops to servers.

Drivers and Hardware Communication

Hardware is diverse. The OS relies on drivers to translate generic requests into device-specific actions: draw a pixel, send a packet, or read a sensor. This driver layer is why the same application can run across many machines without knowing the details of each component.

| Common Device Categories | Storage, graphics, network, audio, and input |

| How the OS Stays Responsive | Interrupts notify the OS when a device needs attention, reducing busy waiting and improving efficiency |

Security Foundations Built into an OS

Security is not a single feature; it’s a stack of small, strict choices. A strong OS uses least privilege, separation, and auditing so mistakes stay contained and suspicious actions leave a trace.

- User accounts and roles with access controls

- Sandboxing to limit what apps can reach, even when they are running normally

- Code signing (where used) to confirm software origin and integrity

- Secure boot concepts to reduce tampering at startup and protect trust chains

OS Choices Shape Everyday Computing

An OS influences what feels “easy.” It affects updates, hardware support, and app ecosystems. It also sets defaults for privacy, file formats, and how quickly you can recover from trouble. These decisions aren’t flashy, yet they define the user experience more than most people expect.

Selection Factors People Often Compare

| Factor | What It Touches |

|---|---|

| Compatibility | Apps, drivers, and file formats |

| Security model | Permissions, updates, and default protections |

| Performance profile | Scheduling, memory, and storage I/O |

| Manageability | Automation, tooling, and long-term support |

Glossary of Everyday OS Terms

| Kernel | The core that manages CPU, memory, and devices with privileged access and strict rules |

| Process | A running program with its own resources, permissions, and address space |

| Thread | A unit of execution inside a process; shares memory while running independently of other threads in timing |

| System Call | The formal door from an app into OS services, requested through a stable API and checked for permission |

| Driver | A hardware translator that turns OS requests into device actions, supporting portability and compatibility |

| Virtual Memory | A managed view of memory that boosts safety, enables sharing, and supports large workloads |

| File System | The structure that stores data with names, permissions, and integrity checks |

| Scheduler | The logic that decides what runs next, balancing responsiveness and throughput |

References Used for This Article

- NIST Computer Security Resource Center — operating system: A concise, official definition of what an operating system is and what it provides.

- Computer History Museum — Operating System Roots: A curated historical overview that discusses early batch monitors including GM-NAA on IBM 704.

- IBM History — The IBM System/360: IBM’s historical record for System/360, the platform era closely tied to OS/360’s mainstream impact.

- IEEE Computer Society History Committee — Compatible Time-Sharing System (1961-1973) Fiftieth Anniversary Commemorative Overview: A detailed historical account of CTSS and the early time-sharing ideas that shaped later systems.

- Bell Labs (Dennis M. Ritchie) — The Evolution of the Unix Time-sharing System: A primary-source narrative describing UNIX’s origins and design trajectory from within Bell Labs.

- University of California, Berkeley — The UNIX Time-Sharing System: A foundational technical paper that documents early UNIX structure and goals, including multiuser design.

- IEEE Standards Association — IEEE 1003.1-2024: The current POSIX.1 standard description for portable operating system interfaces and environments.

- Google Groups (comp.os.minix) — What would you like to see most in minix?: A preserved Usenet thread containing Linus Torvalds’ 1991 announcement of a new free OS project.