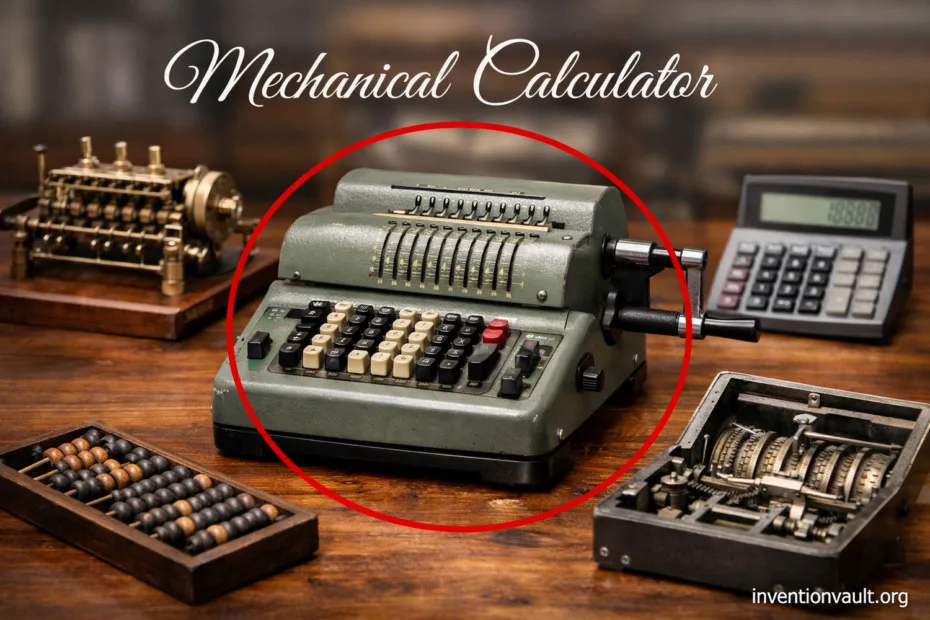

| Invention | Mechanical Calculator |

| What It Is | A mechanical calculator is a device that performs exact arithmetic using gears, levers, and carry mechanisms instead of electronics. |

| Core Purpose | Reliable digit-by-digit results for addition, subtraction, and—on many models—multiplication and division. |

| Earliest Famous Example | Pascal’s calculator (the Pascaline), developed by Blaise Pascal in 1642, built to speed up real-world number work. |

| Major Mechanism Lineages | Gear-and-carry adders, stepped drum designs, pinwheel designs, and key-driven calculators. |

| Typical Inputs | Setting dials, sliders, or a full keyboard; many use a crank to apply motion. |

| Typical Outputs | Number wheels in an accumulator (result register), plus a counter register on many machines. |

| Human Power | Nearly always hand-powered (crank or keys). Some later office machines used a motor, yet the math stayed fully mechanical. |

| Where You’d See It | Desks in business, engineering, education, and any place needing dependable arithmetic before electronic calculators. |

| Why It Matters | It turned arithmetic into a repeatable, auditable action—an important step toward modern computing habits and office workflows. |

A mechanical calculator feels like a small machine built purely for thought. You set digits, apply motion, and watch the accumulator roll to a final value. The charm is real, yet the deeper value is clarity: every turn of a gear train represents a rule of arithmetic, made physical in metal and precision.

What Makes It “Mechanical”

- Exact digits: results are shown on numbered wheels, not estimated scales.

- Carry logic: when a wheel passes 9, a linked mechanism advances the next wheel by 1.

- Registers: many designs separate an input setting area from the result accumulator.

- Repeatable operations: multiplication is often repeated addition, made efficient with shifts and counters.

That combination—carry mechanism, digit wheels, and a controlled way to apply motion—defines the category. A slide rule can be brilliant, yet it is an analog tool. A mechanical calculator is a digit machine: it stores numbers as positions and updates them with dependable mechanical steps.

Inside The Motion

Input Controls

- Sliders that set each digit (common on pinwheel machines).

- Dials that you rotate to a number (common on early adders).

- Keys that directly add digit values (key-driven designs).

- Crank or key action that supplies the movement to compute.

Output And Carry

- Accumulator (result register) with digit wheels.

- Carry levers that advance the next wheel at the right moment.

- Counter register on many models to track repeated operations.

- Reset system to return registers to zero cleanly.

Set digits → Engage mechanism → Update accumulator → Carry to next digit → Read result

When people say a machine “does the math,” this is what they mean: motion becomes state. Every digit wheel is a tiny memory cell. The carry is the rule that keeps the number system honest, so the result register always matches standard arithmetic.

Main Types Of Mechanical Calculator

| Mechanism Family | Common Form | Known For | Typical Trade-Off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gear-and-carry adder | Dial or lever adders | Fast addition, sturdy carry action | Often limited to add/subtract |

| Stepped drum | Crank calculators | Powerful multi-digit operations; historic influence | More parts, heavier feel |

| Pinwheel | Slider-set crank machines | Compact, flexible digit setting | Precise alignment matters |

| Key-driven | Full keyboard machines | Very rapid entry; office-friendly workflow | Large footprint and complex linkages |

| Handheld rotary | Cylindrical pocket devices | Dense engineering in a small body | Smaller display; tight mechanisms |

Gear-And-Carry Adders

These machines focus on addition and subtraction. The key idea is clean carry behavior: when a digit wheel rolls from 9 to 0, the next wheel advances once. You’ll often see simple controls, a clear result window, and a rugged build in cast metal or machined brass.

Stepped Drum Designs

The stepped drum concept is linked to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and his 17th-century work on a calculating device. The “drum” has steps of different lengths, letting one rotation add a chosen digit value into the accumulator. It’s a clever way to pack variable addition into a single rotating part, which is why stepped-drum machines became a classic path to four-function calculation.

Pinwheel Designs

The pinwheel calculator is associated with Willgodt Theophil Odhner in the late 19th century. Instead of fixed steps, it uses adjustable pins that “present” a digit value when the mechanism turns. This made it easier to build compact machines with flexible digit selection. Many well-known desktop calculators followed this approach because it balances power with size.

Key-Driven Calculators

Key-driven machines turn typing into arithmetic. A famous example is the Comptometer, created by Dorr E. Felt in 1887. Each key press can add a value directly to the accumulator, so trained operators could work with impressive speed. This style is deeply tied to office life: rhythm, clean digit entry, and quick corrections without needing to re-crank a cycle every time.

Handheld Rotary Calculators

Some mechanical calculators shrink the whole idea into a pocketable form. The best-known is the Curta, designed by Curt Herzstark and produced starting in the late 1940s. It’s a dense stack of parts: tiny digit setting, a rotating action, and a surprisingly capable carry system. Calling it a small mechnical marvel is fair—its engineering is that tight.

How Multiplication And Division Happen

On many crank calculators, multiplication is built from repeated addition, guided by place value. You set a number once, then apply cycles while shifting the carriage so the same action lands in the tens, hundreds, and beyond. Division is often repeated subtraction with a counter that records how many times the subtract cycle fits. The machine stays exact because every step is a controlled update to the accumulator and its digit wheels.

This matters for understanding what you’re seeing through the windows. Two displays are common: one for the result register and one for a counter that tracks cycles. That counter turns “repeat this action” into a visible number, so the operator can trust the process without guessing where they are mid-operation.

Where Mechanical Calculators Were Used

- Accounting and finance: reliable totals, audits, and ledger work with clear digit displays.

- Engineering offices: routine arithmetic supporting design calculations and measurements.

- Statistics and research: repeated sums and multi-step computations with an exact accumulator.

- Education: demonstrating place value, carry behavior, and structured arithmetic.

- Retail and administration: consistent daily totals in busy workflows.

They also shaped habits. The idea of a register, a clear reset, and a repeatable operation cycle influenced later tools, including early office computing culture. Even now, the physical logic of carry and place value can make arithmetic feel visible in a way a screen does not.

Accuracy And Practical Limits

What It Does Well

- Exact integer math with dependable carry action.

- Repeatability for long sequences of operations.

- Audit-friendly output because digits are always explicit.

Where Care Matters

- Mis-set digits can cascade through repeated operations.

- Wear can dull crisp engagement between parts over decades.

- Dirty mechanisms may affect smooth motion and clean carry timing.

A well-made mechanical calculator can stay accurate for a long time, yet it still depends on clean movement. If a carry action hesitates, the digit wheels can feel “sticky.” That’s not drama; it’s simple mechanics. The good news is that many designs are straightforward to inspect: windows show the state of the number, and the reset tells you whether the registers return cleanly.

Notable Designs That Shaped The Category

Pascaline

Blaise Pascal (1642) helped popularize the idea of a machine that enforces carry rules mechanically. It’s a landmark for addition-focused design and clear digit display.

Arithmometer

Thomas de Colmar patented an arithmometer in 1820, a major step toward broadly used calculating machines. It’s often cited as an early commercially successful mechanical calculator line.

Odhner Pinwheel

Odhner pinwheel concepts (late 1800s) made powerful arithmetic fit into more compact machines. Adjustable pins gave designers a flexible way to represent digits mechanically.

Comptometer

The Comptometer (1887) showed how a keyboard could become arithmetic. Key-driven action made fast addition practical in daily office work, with the accumulator updating on every press.

Curta

The Curta brought a serious mechanical calculator into a handheld form. Its stacked mechanism shows how far precision engineering can go while keeping clear digit output and stable carry behavior.

How To Recognize Key Features On Any Model

- Digit capacity: count how many windows appear in the accumulator to estimate maximum result size.

- Input style: look for sliders, dials, or a keyboard; it hints at the mechanism family.

- Shift system: a moving carriage often signals efficient multiplication through place-value shifting.

- Separate counter: a second register suggests repeated cycles are tracked mechanically.

- Reset controls: strong designs include a clear, consistent way to return registers to zero.

Even without opening a case, these clues tell you a lot. A dedicated counter window implies a deliberate approach to repeated operations. A sturdy shift carriage suggests the machine expects long multiplication workflows. And the feel of the controls—crisp, indexed positions rather than vague motion—often signals a well-engineered carry mechanism and reliable digit engagement.

Care And Preservation Notes

- Keep it dry: stable humidity helps protect steel parts and printed markings.

- Gentle handling: forcing a control can stress a carry linkage or gear mesh.

- Clean storage: dust can migrate into tight clearances over time.

- Servicing: for valuable machines, a specialist familiar with mechanical calculators is the safest path.

Preservation is really about respecting precision. These devices depend on clean engagement between parts, and the tolerances can be surprisingly fine. A calm environment, careful movement, and attention to the reset and carry behavior keep the digit wheels reading true for years.

Why Mechanical Calculators Still Fascinate

They offer a rare mix: function you can see, plus craftsmanship you can feel. A mechanical calculator turns abstract rules into moving parts, so arithmetic becomes a sequence of physical commitments—set, engage, carry, record. That blend of logic and engineering is why these machines remain a favorite subject for collectors, educators, and anyone who enjoys how things work.

References Used for This Article

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History — Early Mechanical Calculators: Documents verified examples of mechanical calculators preserved in a national museum collection.

- Computer History Museum — The Mechanical Calculator: Explains the evolution of mechanical calculating machines and their role in computing history.

- History of Computers — Mechanical Calculators: Provides a structured overview of major mechanical calculator designs and mechanisms.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica — Mechanical Calculator: Summarizes definitions, historical milestones, and core operating principles.

- Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum — Calculating Machines: Describes historically important calculating machines within a major computing museum archive.

- Curta Calculator Museum — History of the Curta: Details the design and significance of the Curta handheld mechanical calculator.