| Technology Name | Geothermal Power (electricity generated by converting subsurface heat into mechanical and then electrical energy) |

| Core Energy Source | Heat inside the Earth (geothermal heat) carried by naturally heated fluids or accessed through engineered circulation pathways |

| Essential Subsurface Ingredients | Heat + Fluid + Permeability; when one element is limited, Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) aim to create a workable reservoir |

| Earliest Human Use | Direct use of hot springs for bathing and heating has a history spanning thousands of years |

| First Documented Geothermal Electricity Demonstration | 4 July 1904 — Larderello (Tuscany, Italy): Piero Ginori Conti produced electricity with a small dynamo driven by geothermal steam, lighting five bulbs |

| Start Of Commercial Geothermal Electricity | 1913 — commercial geothermal electricity from hydrothermal reservoirs is documented as operating by the early 1910s |

| Landmark Flash-Steam Station | Wairākei (New Zealand) — commissioned 1958; recognized as the first to utilize flash steam from geothermal water at that scale |

| Major U.S. Commercial-Scale Development Milestone | 1960 — a 10-megawatt unit at The Geysers (California) is widely cited as an early U.S. commercial-scale step |

| Main Power Plant Types | Dry Steam, Flash Steam (single or double flash), Binary Cycle (closed-loop heat transfer to a secondary working fluid) |

| Typical Temperature Bands Used For Electricity | High-temperature hydrothermal resources often fall around 300–700°F (about 150–370°C) for many power applications; flash commonly uses water hotter than 182°C, while binary can operate at lower temperatures (often around 107–182°C) |

| Standard Reservoir Management Practice | Reinjection of cooled geothermal fluids back underground is commonly used to support long-term resource performance and reduce surface discharge |

Geothermal power is the craft of turning the Earth’s internal heat into dependable electricity. It sits at the intersection of geology, thermal engineering, and careful field management—built around a simple idea: move heat from deep rock to the surface, convert it through turbines or closed-loop cycles, and send the cooled fluids back underground so the system can keep working.

- Geothermal Power Basics

- How Geothermal Electricity Is Made

- Two Places, One System

- Power Plant Types

- Why These Types Exist

- Binary Cycle, Plainly Explained

- Resource Types and Subsurface Requirements

- Hydrothermal Systems

- Enhanced Geothermal Systems

- What Makes A Site Viable

- Milestones In Geothermal Power

- Operational Reality

- What Operators Manage

- Why Reinjection Matters

- Related Geothermal Uses

- Common Questions About Geothermal Power

- Glossary Of Essential Terms

- References Used for This Article

Geothermal Power Basics

- What it converts: Thermal energy in hot water or steam into mechanical rotation and then electricity.

- What makes it distinct: It can supply steady output when the reservoir and equipment are well-matched and well-managed.

- What it needs underground: A workable combination of heat, fluid, and permeability; EGS is designed for places where these do not naturally align.

- Where it fits: Electricity generation, combined heat and power in suitable settings, and—related but separate—direct heat uses such as district heating and geothermal heat pumps.

How Geothermal Electricity Is Made

- Locate a geothermal resource using geology, geophysics, and well data.

- Drill wells to bring hot fluids (or steam) to the surface.

- Separate or exchange heat: steam can go directly to a turbine, or heat can be transferred through a heat exchanger.

- Spin a turbine-generator to produce electricity.

- Condense and cool fluids in a controlled system.

- Reinject cooled geothermal water back underground in many projects to support reservoir performance.

Two Places, One System

| Underground | Surface |

| Reservoir rock holds heat; fractures and pores allow circulation | Turbine converts fluid energy into rotation |

| Hot water or steam rises through production wells | Generator converts rotation into electricity |

| Reinjection can return cooled fluids to help sustain the system | Cooling & condensation close the loop and support stable operation |

Geothermal power is built on continuity: a managed flow of heat and fluids, not a one-time extraction.

Power Plant Types

Modern geothermal electricity is commonly grouped into three plant families. The choice follows the resource: steam versus hot water, and the temperatures available at the wellhead.

| Plant Type | What Drives The Turbine | Typical Resource Fit | Common Variants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Steam | Natural geothermal steam goes directly to the turbine | Steam-dominated, high-temperature fields | Condensing or back-pressure turbine configurations (site-specific) |

| Flash Steam | Very hot pressurized water flashes into steam as pressure drops | Hot-water reservoirs, often >182°C | Single flash, double flash (more than one separation stage) |

| Binary Cycle | Heat transfers to a secondary working fluid in a closed loop | Lower-temperature water, often around 107–182°C | Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC), Kalina-type cycles (working-fluid dependent) |

Why These Types Exist

- Dry steam is the most direct path: steam in, power out.

- Flash steam handles hot water resources by separating steam from liquid as pressure changes.

- Binary expands the playable map by converting moderate heat through a secondary fluid with a lower boiling point.

Binary Cycle, Plainly Explained

In a binary cycle, geothermal water transfers heat through a heat exchanger into a separate working fluid. That secondary fluid vaporizes, turns the turbine, then condenses and repeats—keeping geothermal water and working fluid in their own loops.

Resource Types and Subsurface Requirements

Hydrothermal Systems

- What they are: Natural systems where hot water or steam circulates through permeable rock.

- Why they work well: Nature already provides the plumbing.

- Typical conversion: Dry steam, flash, or binary—depending on temperature and fluid state.

Enhanced Geothermal Systems

- Why they exist: Many regions have hot rock but lack enough natural permeability or fluid movement.

- What changes: Engineers aim to create or improve flow pathways so water can circulate, pick up heat, and return to the surface.

- What it enables: A broader set of locations for geothermal electricity when conditions are suitable and projects are responsibly designed.

What Makes A Site Viable

| Factor | Why It Matters | Typical Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Heat | Higher temperatures support more efficient conversion | Heat-flow data, temperature gradients, well logs |

| Fluid | Water carries heat to the surface and back into the reservoir | Hydrochemistry, pressure tests, flow rates |

| Permeability | Controls how easily fluids move through rock fractures and pores | Well tests, microseismic monitoring, reservoir models |

| Reservoir Management | Reinjection supports long-term performance and reduces surface discharge | Injection strategy, monitoring data, production trends |

Milestones In Geothermal Power

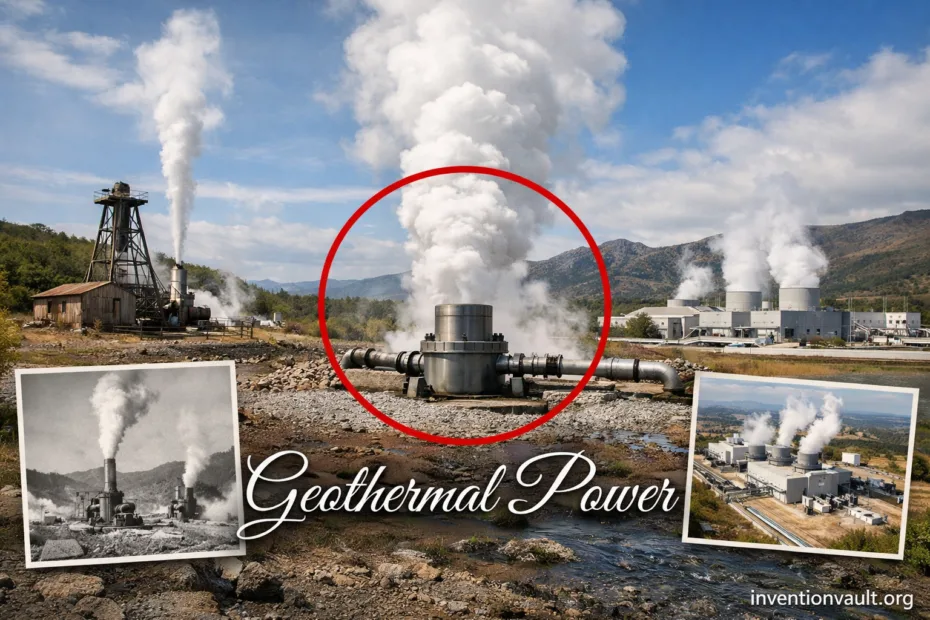

Geothermal power’s history has a clear arc: early experiments proved the concept, commercial plants refined the machinery, and modern projects widened the range of usable resources through improved cycles and better subsurface understanding.

| Year | Milestone | Why It Mattered |

|---|---|---|

| 1904 | Larderello (Italy): Piero Ginori Conti generates electricity from geothermal steam and lights five bulbs | Proof that geothermal steam could drive an electromechanical generator |

| 1913 | Commercial geothermal electricity from hydrothermal reservoirs documented as operating by the early 1910s | Transition from demonstration to sustained power production |

| 1958 | Wairākei (New Zealand) commissioned; early large-scale use of flash steam from geothermal water | Showed that liquid-dominated resources could be converted efficiently |

| 1960 | The Geysers (California): early U.S. commercial-scale development highlighted with a 10-megawatt unit | Anchored geothermal electricity as a practical utility-scale resource |

| 1970 | Reinjection begins appearing as a widely recognized method to extend reservoir life and manage spent fluids | Set the stage for long-lived fields through better reservoir stewardship |

| 1970s | Early hot dry rock experiments in the United States | Helped shape the technical foundations of modern EGS thinking |

Operational Reality

What Operators Manage

- Flow balance: aligning production and injection to protect reservoir performance.

- Fluid chemistry: mineral scaling and corrosion risks are addressed through engineering choices and monitoring.

- Heat utilization: matching the plant cycle to the available temperature and fluid state.

- Non-condensable gases: some reservoirs contain naturally occurring gases; facilities use controls appropriate to the plant design.

Why Reinjection Matters

Reinjection is widely used to return geothermal water to the subsurface. It supports responsible resource use, helps manage spent fluids, and is commonly cited as a practical way to extend reservoir life when applied in a site-appropriate manner.

Related Geothermal Uses

Geothermal energy is broader than electricity. Many regions use geothermal heat directly for district heating, industrial heat needs, greenhouse heating, and building comfort through geothermal heat pumps. These pathways share the same resource—Earth heat—while using different temperature levels and equipment.

| Use | Typical Temperature Need | Core Idea |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | Medium to high temperatures (cycle-dependent) | Convert heat to mechanical work, then electricity |

| District Heating | Often lower than power-generation needs | Deliver hot water heat directly to buildings |

| Geothermal Heat Pumps | Shallow ground temperatures | Move heat efficiently between buildings and the ground |

Common Questions About Geothermal Power

Is Geothermal Power Renewable?

Geothermal energy is commonly treated as renewable because the Earth continuously produces heat, and many geothermal projects use reinjection to support long-term reservoir performance.

Why Can Geothermal Electricity Be Steady?

When the reservoir supplies stable heat and fluids, geothermal plants can run for long periods with predictable output, shaped more by maintenance planning than by daily weather changes.

What Determines Dry Steam, Flash, or Binary?

The deciding factors are the state of the fluid (steam or water) and its temperature. Dry steam uses steam directly, flash converts very hot water into steam as pressure drops, and binary transfers heat to a secondary working fluid in a closed loop.

What Is EGS In Simple Terms?

Enhanced Geothermal Systems target hot rock that lacks enough natural permeability or fluid. The goal is to create a usable circulation pathway so heat can be carried to the surface for power generation.

How Does Reinjection Help?

Reinjection returns geothermal water to the subsurface, supports responsible fluid management, and is commonly cited as a method to help extend reservoir life in many geothermal developments.

Glossary Of Essential Terms

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Hydrothermal | Naturally occurring geothermal system where hot water or steam circulates through permeable rock |

| Permeability | How easily fluids move through rock fractures and pores |

| Flash Steam | Steam created when very hot pressurized water partially boils as pressure decreases |

| Binary Cycle | A closed-loop system that transfers geothermal heat to a secondary working fluid |

| Reinjection | Returning cooled geothermal fluids back underground to support reservoir management |

| EGS | Approach that aims to access heat in hot rock where natural permeability or fluid is limited |

References Used for This Article

- U.S. Department of Energy — Enhanced Geothermal Systems: Defines EGS and explains the heat–fluid–permeability framework.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration — Geothermal Power Plants: Summarizes plant types and notes typical high-temperature resource ranges used for power.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration — Geothermal Timeline: Provides milestone dates such as early plant development and reinjection adoption.

- OSTI.GOV — Eighty Years Of Electricity From Geothermal Steam: Documents the 4 July 1904 Larderello demonstration and its historical significance.

- International Renewable Energy Agency — Geothermal Energy: Notes commercial geothermal electricity operations since 1913 and outlines major technology pathways.

- UNFCCC — Geothermal Power Plants: Describes dry steam, flash, and binary plants and links them to temperature bands.

- California Energy Commission — Types Of Geothermal Power: Explains how geothermal plant types convert heat to electricity, including binary cycle operation.

- Engineering New Zealand — Wairākei Geothermal Power Development: Records Wairākei’s 1958 commissioning and its role in flash-steam geothermal history.

- U.S. Geological Survey — Geothermal Energy And USGS Science: Provides a clear overview of geothermal use over time and modern resource assessment directions.