| Invention Name | Fax Machine (facsimile) for documents over telephone lines |

| Core Idea | Turn a page into a line-by-line signal, send it as audio tones, rebuild the same page image at the other end |

| Early Pioneer | Alexander Bain (British patent dated 27 May 1843) describing an early facsimile method |

| Key Early Improvement | Frederick Bakewell (1848) refining the concept with synchronized rotating cylinders |

| First Practical Service | Giovanni Caselli and the pantelegraph (commercial use in the 1860s) for handwriting and signatures |

| Modern Office Milestone | Xerox LDX introduced in 1964; Xerox Magnafax Telecopier sold in 1966 and designed for a standard telephone line |

| Primary Network | PSTN (public switched telephone network), using the same kind of voice-grade channel a phone call uses |

| Standards That Enable Compatibility | ITU-T T.30 for the session “conversation”; ITU-T T.4 for the page image coding; ITU-T T.38 for real-time fax over IP |

| Typical G3 Image Detail | About 203×98 dpi (standard) or 203×196 dpi (fine) for black-and-white documents |

| Typical Speeds | Common G3 rates around 9.6–14.4 kbps; Super G3 can reach up to 33.6 kbps under good line conditions |

| Common Compression | Modified Huffman (MH) is a classic baseline; options include MR and MMR; many Super G3 devices also support JBIG |

| Output Methods | Older units often used thermal paper; later designs commonly print on plain paper using inkjet or laser engines |

A fax machine is a document copier that speaks in telephone tones. It scans a page into a simple black-and-white map, squeezes that map with compression, then sends it through a normal line so another device can rebuild the same printable image. The clever part is not just the scan or the print—it is the standard handshake that lets two machines agree on speed, detail, and error control before the first line is sent.

- What “Fax” Really Means

- What Travels Over The Line

- How Fax Transmission Works

- Key Parts Inside A Fax Device

- Document Handling

- Scanner And Image Engine

- Fax Modem And Line Interface

- Fax Standards And Compatibility

- Fax Types And Subtypes

- Standalone Fax Machines

- Multifunction Printers With Fax

- Computer Fax Modems And Software

- Digital Delivery Variants

- A Short Technical Timeline

- Page Quality, Speed, And Why White Space Helps

- Why Fax Still Shows Up In Modern Workflows

- References Used for This Article

What “Fax” Really Means

Fax is short for facsimile, meaning a faithful copy. In practice, that copy is a raster image: a grid of dots that represent ink and paper. Even when you send a clean typed letter, the machine treats it like a picture made of tiny black marks.

What Travels Over The Line

Modern faxing is digital, yet it rides a channel built for voice. The page becomes bits, the bits become tones, and the tones become a recoverable page at the far end. That’s why fax can work on a simple wall jack—and why line noise can still matter to speed and clarity.

How Fax Transmission Works

- Scan the sheet line by line (flatbed or ADF), producing a bitmap of black and white dots.

- Normalize the image: the device picks a resolution and builds a consistent page grid so both sides interpret the dots the same way.

- Negotiate using handshake tones: the machines agree on speed, coding, and error handling.

- Compress long runs of white space and repeated patterns with fax coding so a mostly blank page does not waste time.

- Modulate the compressed bits into audio suitable for the line, then send and receive in controlled blocks.

- Rebuild the bitmap at the far end, then print or store it in memory so the message survives even if the line drops right after.

| Stage | What Happens | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Call Setup | A standard phone call is established over the PSTN. | Fax uses a familiar path that exists in many buildings already. |

| Negotiation | Devices trade capabilities: resolution, coding, speed. | Compatibility stays high, even between an old unit and a newer MFP. |

| Page Transfer | Compressed raster data is sent as tones with defined framing. | It remains readable with ordinary line quality—though a noisy line can slow things down. |

| Reproduction | The receiver decompresses and prints, or stores the page in memory. | A fax can recieve pages even when no one is standing next to it. |

A Closer Look At The “Fax Sounds”

The squeals and chirps are not random. They are modem tones that carry structured information: “Here is my speed,” “Here is my coding,” “Here is a page block.” When both sides agree, the sender streams a compressed bitonal image so the receiver can rebuild the page exactly.

That negotiation is a big reason fax became dependable in offices. A machine that only supports basic settings can still complete a call by falling back to a more modest mode. It feels old-fashioned, yet the design is quietly robust and very predictable under real phone-line conditions.

Key Parts Inside A Fax Device

Document Handling

- ADF rollers to feed a stack of pages with steady motion.

- Flatbed glass for books, receipts, and anything that cannot be bent.

- Paper path sensors that prevent a skewed page from becoming a distorted scan.

Scanner And Image Engine

- Optical sensor that turns light and shadow into a line signal.

- Thresholding that decides what is “ink” and what is “paper” for clean bitonal pages.

- Compression logic that shrinks large white regions using fax coding.

Fax Modem And Line Interface

- Dialing and call control for the PSTN.

- Handshake logic that negotiates speed and mode.

- Tone modulation that carries bits through a voice channel.

Fax Standards And Compatibility

Fax works globally because it behaves like a polite guest: it asks what the other side can do, then sticks to a shared set of rules. Those rules are formal telecom recommendations that define the call “conversation,” the page coding, and—today—the bridge between fax and IP networks. If you understand three names, you understand most of the modern fax world: T.30, T.4, and T.38.

| Standard | Defines | Where You See It |

|---|---|---|

| ITU-T T.30 | The procedure for a fax call: negotiation, control signals, and orderly page transfer. | Every classic Group 3 fax session over a standard phone line. |

| ITU-T T.4 | How the page is coded, including classic MH and optional 2D methods. | Most office faxes and fax modems, especially for text-heavy pages. |

| ITU-T T.6 (related) | Group 4 coding control functions, including MMR for efficient 2D compression. | Higher-efficiency error-controlled workflows and some digital fax environments. |

| ITU-T T.38 | Real-time fax over IP, designed to carry fax reliably across packet networks. | Gateways, VoIP systems, and “FoIP” deployments that still must talk to G3 devices. |

Fax Types And Subtypes

The word fax covers a family of devices. Some are built as dedicated hardware, others are features inside a larger machine, and newer services can act like a fax endpoint without printing anything until you choose. The shared thread is the same: raster scanning, standard negotiation, and a recoverable page delivered across a telecom link.

Standalone Fax Machines

Classic standalone units combine scanner, fax modem, and a printer in one box. Older models often used thermal paper rolls, while later designs shifted toward plain-paper printing with inkjet or laser engines.

Multifunction Printers With Fax

An MFP (printer/scanner/copier) can add fax as a telecom module. The scanner creates the page image, internal memory buffers it, then the fax board handles negotiation and tone transmission. You get a familiar fax workflow with modern print quality.

Computer Fax Modems And Software

A computer with a fax modem can act as a fax endpoint, creating and receiving pages as files instead of paper. The same concepts apply: handshake, coding, and bitonal images. It feels cleaner because documents are stored and searchable, yet it still speaks the same fax language.

Digital Delivery Variants

- Fax over IP (FoIP): aims to carry fax reliably across packet networks, often using T.38 in real time.

- Store-and-forward fax: the page is handled as a file, moved through a digital system, then delivered as a fax-compatible call at the edge.

- Hybrid gateways: translate between a physical fax machine on one side and a cloud endpoint on the other, keeping legacy devices useful.

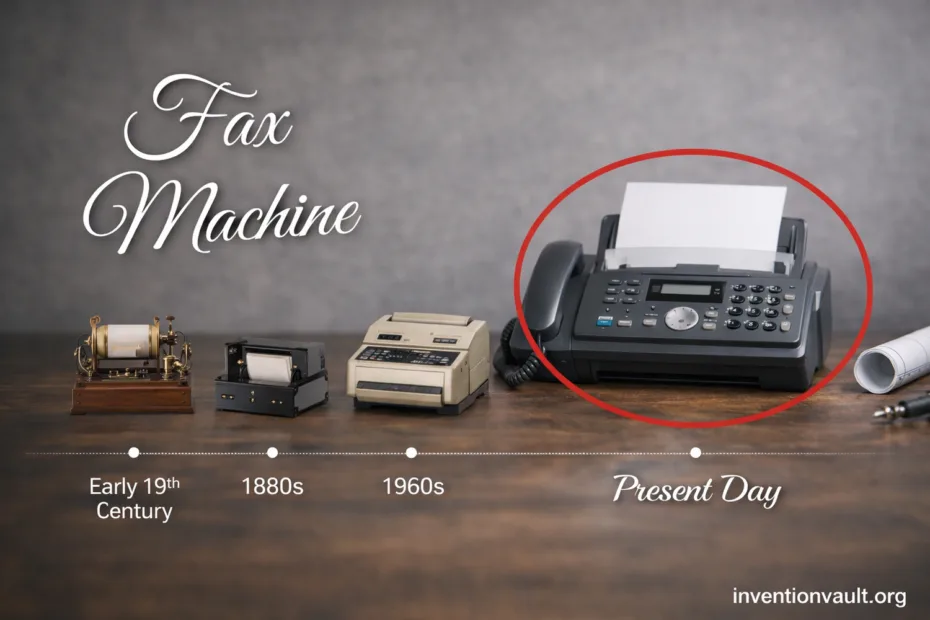

A Short Technical Timeline

| Period | What Changed | Why People Cared |

|---|---|---|

| 1840s | Bain and Bakewell explored early image telegraph ideas using synchronized motion and conductive patterns. | It proved a page could be treated as data, not just ink. |

| 1860s | Caselli’s pantelegraph enters practical service, transmitting signatures and handwriting. | Secure-looking copies became possible at a distance, which mattered for paperwork. |

| 1964–1966 | Xerox moves fax toward modern office life with LDX and then the Magnafax Telecopier on standard lines. | Fax becomes an approachable business tool rather than a specialist lab system. |

| 1980 | International standardization of Group 3 facsimile helps create broad interoperability. | Different brands can reliably exchange pages, helping fax spread quickly. |

| Late 1990s | Fax adapts to the internet era with real-time T.38 methods over IP networks. | Fax survives changes in telecom infrastructure while keeping the same call behavior. |

Page Quality, Speed, And Why White Space Helps

Fax compression is built for typical paperwork: lots of white background, sharp text, and repeated horizontal patterns. A page with large blank areas often transmits faster because runs of white dots compress very well. A page filled with heavy shading can take longer because the machine must describe far more changes from dot to dot, even if the message is short. It’s a simple idea with real impact on time and clarity.

| Setting | What You Get | Typical Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Standard (~203×98 dpi) | Readable text for everyday forms, simple drawings, and clean signatures. | Often faster because fewer scan lines must be described. |

| Fine (~203×196 dpi) | Sharper small text and tighter line art, especially on dense documents. | More data, usually more time on the same line conditions. |

| Compression Choice | MH is common; MR/MMR/JBIG can improve efficiency for some pages. | Better compression can reduce on-line time for pages with repeating structure. |

Why Fax Still Shows Up In Modern Workflows

Fax persists because it delivers a fixed page image with a predictable delivery pattern. It can be integrated into systems that expect paper-like documents, signatures, stamps, and handwritten notes. Many organizations also value the straightforward point-to-point feel: one device calls another, exchanges capability tones, and transfers a page without needing a shared login or a shared file space. That simplicity can be surprisingly attractive when people want consistency, traceability, and a print-ready record.

Fax is old, yet the idea is timeless: a page becomes a signal, then becomes a page again.

References Used for This Article

- GOV.UK — Public Switch Telephone Network (PSTN): Defines the PSTN and explains its role and transition in modern telephony.

- ITU — T.30: Procedures for document facsimile transmission in the general switched telephone network: Describes the core call setup and session procedures used by classic fax systems.

- ITU — T.4: Standardization of Group 3 facsimile terminals for document transmission: Specifies Group 3 fax image coding and interoperability requirements.

- ITU — T.38: Procedures for real-time Group 3 facsimile communication over IP networks: Explains how fax is carried reliably over IP networks in real-time FoIP deployments.

- Library of Congress — ITU-T Group 4 FAX Compression (T.6): Summarizes the bitonal compression approach (MMR) used for efficient facsimile page encoding.

- Smithsonian — Caselli Pantelegraph: Documents a museum-held early facsimile system linked to practical 1860s image transmission.