| Detail | Analytical Engine |

|---|---|

| Name | Analytical Engine (a proposed general-purpose mechanical computer) |

| Primary Designer | Charles Babbage (English mathematician and inventor) |

| Concept Introduced | Developed as a new design in the late 1830s, after work on the Difference Engine |

| Intended Power Source | Steam-driven mechanical motion, supervised by an operator (not an “automatic electric” machine) |

| Number System | Planned around decimal digits (wheels representing 0–9), rather than binary |

| Main Modules | Mill (calculation), Store (memory), Reader (input), Printer (output) |

| Program Input | Punched cards, inspired by Jacquard-style card control |

| Planned “Memory” Capacity | Often described as storing about 1,000 numbers; sources vary on digit length (commonly cited around 40–50 digits per number, depending on the design stage) |

| Control Features | Designed to support conditional branching and repetition (looping) through mechanical control |

| Build Status | Never completed as a full machine in Babbage’s lifetime; a portion (including a mill and printing mechanism) was completed later |

| Key Contributor | Ada Lovelace wrote influential notes describing how programs could drive the machine (including a worked example for Bernoulli numbers) |

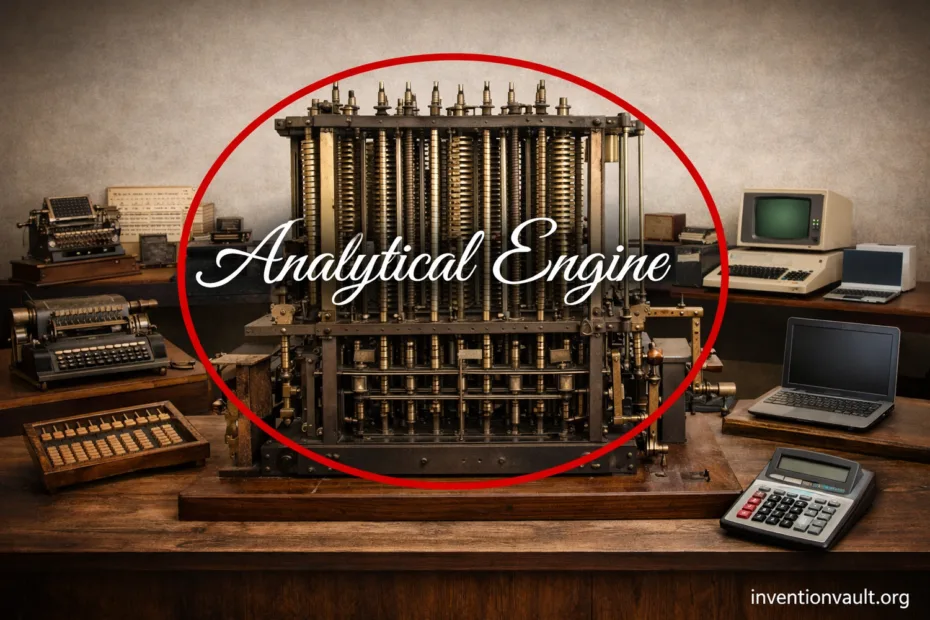

Analytical Engine was a blueprint for a programmable mechanical computer—a machine that would follow instructions and manipulate data in a controlled sequence. It reads as startlingly modern: a CPU-like “mill”, a memory-like “store”, and input/output devices built around cards and printing.

What Made It Different

- General-purpose design rather than a single fixed calculation.

- Programs on punched cards, so the same hardware could run many computations.

- Separate data and operations, echoing how later computers treat memory and instructions.

- Branching and repetition planned into the control system, enabling complex workflows.

Design Anatomy

The Mill

The mill was the calculating core, built to perform arithmetic on numbers pulled from the store. Think of it as a mechanical processor where gears stand in for logic.

- Addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division were central targets.

- Digit wheels and carry mechanisms would move values with precision.

The Store

The store was planned as mechanical memory holding intermediate values and final results. Designs are commonly summarized as about 1,000 numbers of around 40–50 digits, a scale meant for serious table-making and research.

- Numbers would be stored in columns of digit wheels.

- Results could be reused without re-entering data each time.

Control and Flow

The control system aimed for sequencing, repetition, and conditional branching. That meant a program could do one step, test a value, then jump to a different step—teh kind of flexibility that separates a calculator from a true computer.

- Loops for repeated operations.

- Decisions based on computed values.

Input

Input was planned through punched cards read by a reader. Cards would carry both instructions and values, bringing industrial card control into mathematics.

- Instruction cards define operations.

- Number cards supply constants and data.

Output

Output was designed to be useful, not ornamental. A printer could produce tables directly, reducing transcription errors. Some plans also mention output to punched cards, so results could be re-used as future input.

- Printed tables for scientific and financial work.

- Repeatable output to support chained calculations.

From Cards to Programs

The punched-card approach mattered because it made behavior portable. Swap the card stack and the same machine becomes a new program. That idea—hardware staying put while instructions change—sits at the heart of modern computing.

Card Roles in Plain Terms

- Operation cards tell the machine which math action to perform.

- Variable cards indicate which stored values to read or write.

- Number cards supply explicit constants when needed.

This division helps explain why the Analytical Engine feels familiar. It separates data from instructions and lets each be handled with structure rather than improvisation.

Key Milestones and Documents

| Year | What Happened | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| 1830s | Analytical Engine emerges as a new plan beyond the Difference Engine. | Marks the shift from a single-purpose calculator to a programmable design. |

| 1840s | Public explanations spread through lectures and technical writing; the idea becomes shareable. | Introduces the machine’s architecture to a wider scientific audience. |

| 1843 | Ada Lovelace publishes detailed notes describing how programs could run on the engine. | Shows the leap from “machine” to software thinking. |

| 1871 | Babbage dies with the full engine still unbuilt. | Highlights how far the design pushed precision engineering of the era. |

| 1910 | A portion of the engine (including a mill and printing mechanism) is completed later. | Demonstrates that key pieces were mechanically achievable. |

Why It Was So Hard to Build

Even with a strong concept, a mechanical computer of this scale demanded extreme precision. Thousands of parts had to align, carry digits reliably, and resist wear under continuous motion. Add in evolving plans and limited industrial tooling, and the engineering gap becomes clear—without needing any dramatic story.

Precision at Scale

Reliable carry mechanisms and alignment were non-negotiable. A small slip could corrupt a long-digit result. That is the quiet enemy of every gear-based calculator, amplified into a full computer.

Complex Control

A design that supports branching and loops needs a control system that can switch paths cleanly. Doing that with purely mechanical logic is possible, yet demanding. The elegance is real; the tolerance budget is brutal.

How It Maps to Modern Computing

The Analytical Engine is often explained with modern labels because the parallels are direct. Mill aligns with a processor, store aligns with memory, and the reader/printer cover input/output. The deeper link is the program concept: a finite list of steps that can repeat, branch, and reuse values.

- CPU concept: a central unit that applies operations to data.

- Memory concept: stored values accessible by position.

- I/O concept: separate mechanisms for feeding in and extracting results.

- Program flow: repetition and conditional jumps, not only straight-line steps.

Common Confusions Cleared Up

It is easy to mix the Analytical Engine with the Difference Engine. The Difference Engine targets a specific job—generating numerical tables via repeated differences—while the Analytical Engine targets a general job: executing a chosen program using stored data.

Another frequent confusion is thinking it was a completed Victorian computer that quietly ran in a lab. The historical reality is simpler: the full machine remained unbuilt, yet the architecture was articulated in enough detail that later engineers could recognize a true computer blueprint—not a vague sketch.

References Used for This Article

- Science Museum (London) — Babbage’s Analytical Engine: Official museum documentation describing the design, purpose, and surviving components of the machine.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica — Analytical Engine: A concise scholarly overview of the engine’s architecture, history, and significance.

- Computer History Museum — Babbage’s Engines: Curated historical material explaining how the Analytical Engine differed from earlier calculating machines.

- University of Cambridge — Babbage Papers Collection: Academic archival resources detailing original drawings, notes, and correspondence.

- British Library — Ada Lovelace’s Notes on the Analytical Engine: Primary-source material illustrating early ideas of programming and algorithmic thinking.

- The Royal Society — Charles Babbage Archive: Institutional records outlining Babbage’s scientific work and mechanical computing concepts.